Following Leon Spink’s huge upset victory over Muhammad Ali in 1978, the heavyweight championship belt was torn in two. The World Boxing Council soon stripped Spinks of their title after he refused to obey their order to defend against Ken Norton. Larry Holmes then defeated Norton for that version of the world crown, while the rival World Boxing Association recognized Spinks. After Ali defeated “Neon Leon” in the rematch and then retired, Spinks fought little-known contender Gerrie Coetzee. To the shock of many, the unknown South African demolished the former champion in one round, flooring him three times with his so-called “bionic” right hand.

Ali retired and the WBA then matched Coetzee with top contender John Tate for their version of the championship. The bout took place in Pretoria, South Africa and it represented the first time a South African fought for any version of the world heavyweight title. Tate won a unanimous decision, but the contest raised eyebrows for one simple question: why was a championship fight taking place in a country universally reviled for its racist apartheid policies and its brutal treatment of its own citizens? Further, why was a black American athlete a willing participant? The answer, of course, was simple: money.

After Tate lost his title in his first defense, suffering a shocking, one-punch KO to the unheralded Mike Weaver, Bob Arum and the WBA put together Weaver vs Coetzee, a showdown for the other title belt, but the organizers had an answer for those condemning the staging of another championship match in South Africa. This time the event was held not in Pretoria, but in Sun City, the resort town set up in the “puppet state” of Bophuthatswana. Everyone knew where the money made from the event was really going, but Arum and company could assert with a straight face that the match was not happening in the global pariah that was apartheid South Africa.

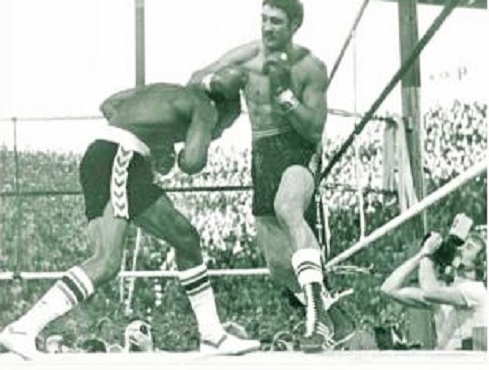

Few knew what to expect from the contest between two of the heavyweight division’s most enigmatic fighters. Coetzee had been competitive against Tate before he tired but, Spinks aside, he had yet to defeat a viable top contender. Weaver had no fewer than nine losses on his record though the year previous he had surprised everyone by giving Larry Holmes a hard-fought and exciting battle in Madison Square Garden.

One thing was for certain: both could punch. Coetzee had demonstrated this in his demolition of Spinks, his surgically repaired right hand a genuine threat, while Weaver had fifteen knockouts in twenty-two wins and had badly hurt Holmes before going on to ruin Tate with a single left hook.

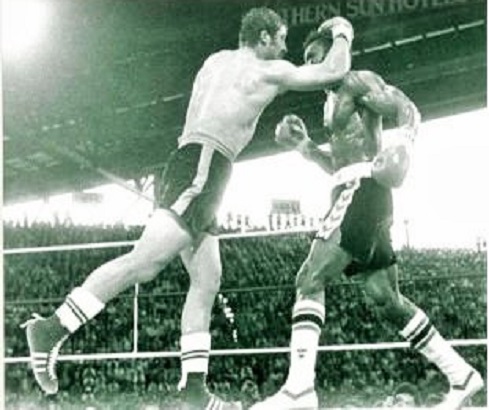

And indeed it was power which decided the outcome in the end. Weaver vs Coetzee was a rather ugly fight, but it was not wanting for action as it boasted some thrilling moments, plenty of toe-to-toe slugging, and a sudden ending. The reason for the contest’s unsightliness was simple: as his loss to Tate showed, Coetzee lacked the stamina to battle in the trenches for fifteen rounds. Knowing this, the challenger’s strategy was to try and ambush Weaver and score the early knockout. But when that plan failed he relied on clinching and wrestling to slow the pace and limit exchanges.

Midway through the first round, and with visions of his blitzing of Spinks in his mind, Coetzee brought the crowd to its feet as he unleashed a volley of powerful ‘bionic’ rights. Weaver stood up to the barrage but those at ringside noticed him blinking his eyes and they wondered if he was dazed from the blows. Between rounds, Weaver’s corner sprayed his eyes with water; it would later be determined that a liniment rubbed on the South African’s chest and shoulders was the culprit. Weaver kept blinking through rounds two and three while Coetzee tried in vain to finish matters with one big right hand.

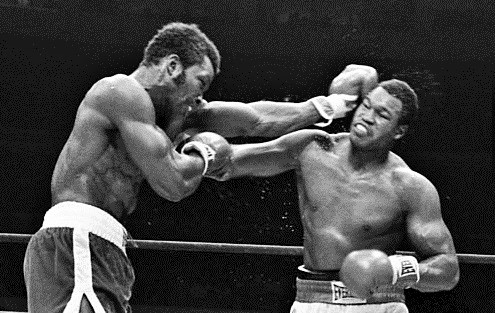

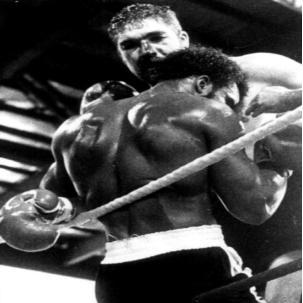

For the next few rounds the two heavyweights rumbled like a pair of bull elephants, taking turns blasting each other with haymakers. There appeared no strategy other than Weaver’s work to the body and Coetzee’s frequent clinching and leaning, a tactic obviously meant to tire his opponent. Otherwise the two men just came together over and over again and unloaded heavy shots, both throwing and both catching. While not exactly an impressive exhibition in terms of advanced ringcraft, for enthusiasts of brutal, heavyweight slugging, Weaver vs Coetzee was just the ticket.

The turning point came in a blistering round eight. Coetzee got home a huge right that put Weaver on the ropes and the challenger, sensing a chance to end it, unloaded with everything he had. As the crowd roared, the South African landed one right hand after another and it seemed as if any moment his American foe would have to cave in from the onslaught. But Weaver, showing astonishing toughness and composure, withstood the attack and even landed some potent blows of his own before round’s end. At the bell a deflated Coetzee trudged wearily back to his corner; he had landed his best punches but Weaver was still on his feet and fighting back.

In the succeeding rounds Coetzee resorted to more clinching and wrestling and Weaver became increasingly frustrated. In the eleventh the champion opened the bridge of Coetzee’s nose with a right hand; in the twelfth he snapped his head back with an uppercut. All the while the South African was grabbing and hugging and draping himself over Weaver like a lovelorn teenager in a slow dance competition. The champion complained to the referee but Coetzee persisted with his mauling tactics.

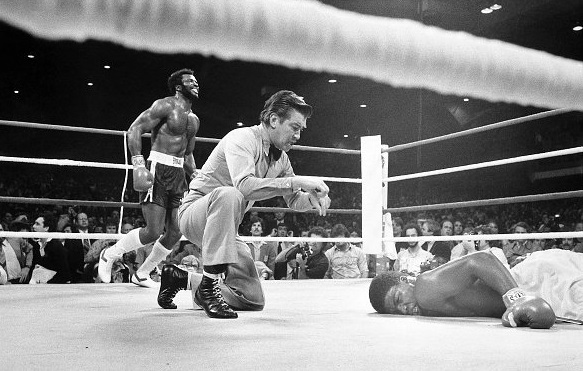

An exasperated Weaver decided enough was enough in round thirteen. He abruptly reversed the momentum and began stalking with purpose, connecting with a right hook, followed by some heavy shots to the challenger’s body, and then another right that put the South African on the run. Showing more energy than at any previous point in the battle, Weaver then struck with a series of stinging jabs before Coetzee attempted to stand his ground in ring center and time the champion with a “Hail Mary” right-hand haymaker.

But the blow never landed; instead Weaver beat the South African to the punch with his own thunderous right which connected flush on Coetzee’s chin. Down went Gerrie. He tried to rise but was still on his knees when the referee finished the count. Fittingly, a slugfest between two power punchers ended with a clean, one-shot knockout.

Weaver would go on to beat James Tillis before losing his title to Michael Dokes in a highly controversial bout. Coetzee then defeated Dokes to become South Africa’s first-ever heavyweight belt-holder, the match taking place in Ohio, not Sun City. All the while, Larry Holmes was universally recognized as the real heavyweight champ, thanks in part to his win over Weaver. But Holmes vacated his WBC title to avoid a fight with Greg Page, and also to make a big money unification match with Coetzee that, for various reasons, never happened. Instead Page knocked out Coetzee, while Tim Witherspoon became the WBC title-holder. The chaotic heavyweight title mess had begun in earnest and confusion reigned for years before a young man with dynamite in his fists came along to impose order. His name was Mike Tyson. – Michael Carbert