In the course of reading Tris Dixon’s ground-breaking book, Damage: The Untold Story of Brain Trauma in Boxing, a poignant quote from renowned novelist and fight scribe Budd Schulberg kept echoing in my mind: “As much as I love boxing, I hate it. And as much as I hate it, I love it.”

Schulberg’s words resonate as they encapsulate the reality of being a boxing fan, especially in our time, when the risks are much better understood. For all the elevated talk of pugilism being “The Sweet Science,” or “the manly art of self-defense,” it is a brutally violent sport. And Dixon’s book does an excellent job of not only reminding us of this sobering reality, but of bringing to the forefront the wreckage often left behind and overlooked. The reality that many of our favorite fighters, whose courage we deeply admire and whose best performances we watch repeatedly, suffer in a decrepit state when their careers are over is an agonizing truth we all avoid contemplating. It is clear Dixon believes that, for fans and fighters alike, contemplate it we must.

The first few chapters of Damage discuss the medical history of brain trauma in pugilism, beginning with an exploration of the earliest awareness of “punch-drunk syndrome,” which was first recognized medically in the late 1920s. The book then charts the evolution of our understanding of this condition over the years and decades since. Dixon details for us the precise meanings of the medical terms “dementia pugilistica” and “chronic traumatic encephalopathy,” enabling readers without medical degrees to understand with clarity what happens to the brains of prizefighters whose skulls absorb thousands of hard blows over the course of a lengthy career.

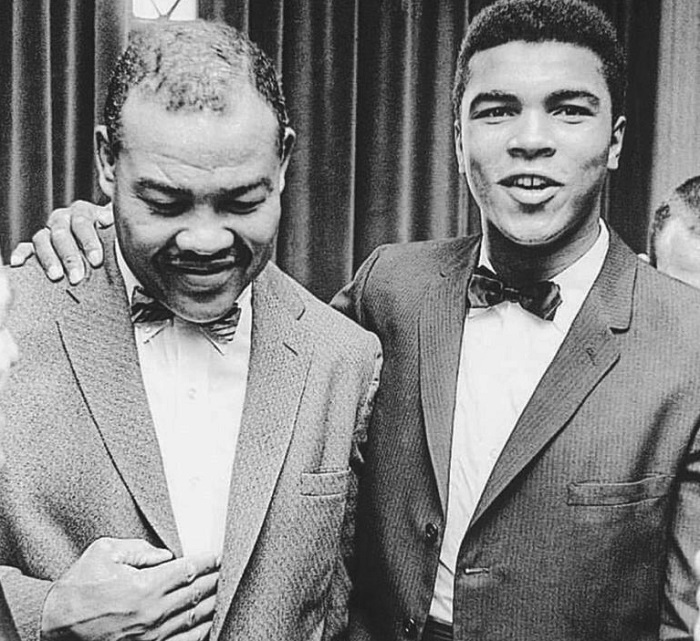

Woven through this engaging history are many heartbreaking accounts of pugilists reduced to a shell of their former selves in their post-boxing years. The long list includes such all-time greats as Ad Wolgast, Terry McGovern, Battling Nelson, Sugar Ray Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis and Henry Armstrong. All paid a regrettable price for their success in the ring. But while Dixon’s treatment of this material and his desire to be thorough are laudable, he runs the risk of overwhelming the reader with a plethora of sad stories. I found myself hungering for fewer examples, but more depth and detail.

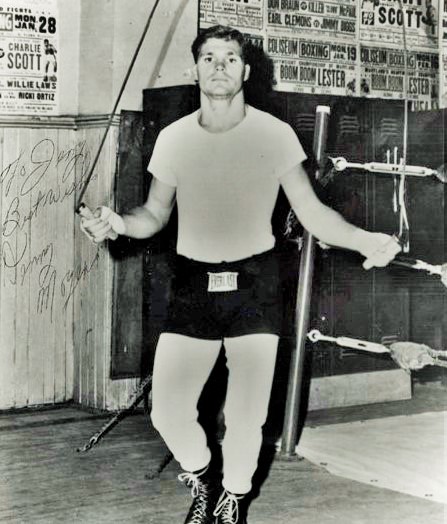

As if anticipating such a response, Dixon gives extra attention to the absorbing tale of the Moyer family in the chapter entitled “Buried Alive.” Denny and Phil Moyer were brothers in boxing and both enjoyed a degree of success. Denny competed in 141 fights between 1957 and 1975, while Phil fought 39 bouts from 1957 to 1969. Collectively they shared the ring with such legends as Sugar Ray Robinson, Carlos Monzon, Nino Benvenuti, Emile Griffith, and Florentino Fernandez. But both fought on too long and in their later years their health deteriorated to the point they required around-the-clock care. Dixon paints a vivid and disturbing picture of their plight as they “muddled around the hallways of a nursing home in Oregon, confused. They wore bicycle helmets in case they fell, clung to metal frames while shuffling down empty corridors.”

As difficult as it is to read about fighters like Denny and Phil Moyer, it is important for all of us to remember and understand their plight. But Damage is about much more than telling tragic tales and reminding us of the dark side of the fight game. The book also offers hope by highlighting valuable recommendations which could reduce the risks moving forward and help us find ways to protect the long-term health of boxers.

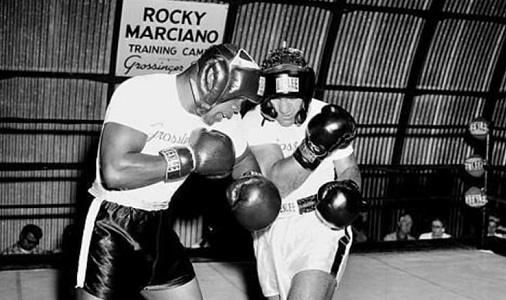

The single recommendation that stands out the most for me is that fighters should reduce significantly the amount of sparring done in training. Dixon cites Dr. Robert Cantu, one of the world’s leading neurologists and an expert on concussions, who urges all boxers to deviate from the typical old-school approach where more is always better. In his opinion, fighters should focus on conditioning and cardiovascular exercise, while refining their fighting technique outside the ring, with their trainer or on the punching bags. He applauds the growing trend of boxers “staying away from sparring except right before a fight.”

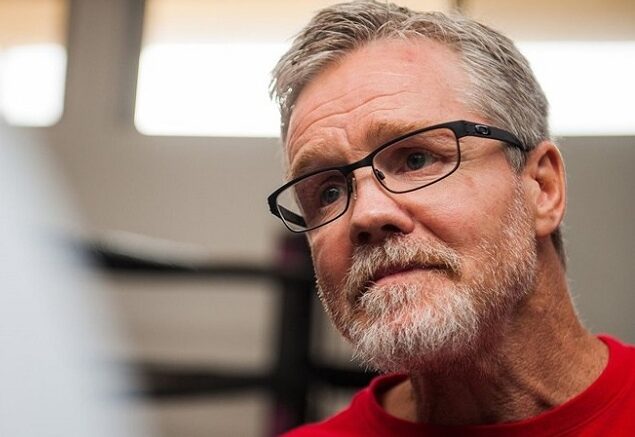

Renowned trainer Freddie Roach shares Cantu’s outlook when it comes to sparring. Roach was a contender in the 1980s and he has suffered from Parkinson’s Syndrome for many years, the result of his boxing career. If there’s one person that young fighters today would likely listen to, it’s Roach.

“My whole career,” he tells Dixon, “I sparred six days a week. Every day I trained, I sparred. Now I get guys who spar one day, I see the mistakes they made and what they need to improve on, I study the sparring, and the next day on the mitts we practice… I think six days a week was crazy, three days a week maybe—still pushing it a little bit—two days is better. Can you get away with not sparring? No, I don’t think so. I think timing and distance and things of that nature have to be adjusted and can only be adjusted in sparring. [But] I think fighters overspar and I think that has a lot to do with the problems.”

In addition to reducing the frequency of sparring, Dixon emphasizes another key recommendation: minimizing ring contact for young kids. This may seem obvious, but sadly, many fighters experience significant head trauma at an early age. Dr. Charles Bernick, who currently leads the Professional Fighters Brain Health Study in Las Vegas, says that full contact boxing should not begin before the age of fourteen.

“The brain doesn’t really completely form or stop its development until you’re in your twenties, but certainly around twelve, thirteen, fourteen, there’s a time when a lot of changes in the brain are occurring,” explains Bernick. “So the earlier you start, it may predispose you to either greater deficits or increase your likelihood of getting certain diseases.”

Such concrete information from genuine experts in the field is a major part of what makes Damage an important book for everyone involved in boxing. Even if only a handful of trainers and fighters read it and heed its advice, this would result in any number of ring warriors potentially avoiding long-term injury and suffering. But one senses that Dixon’s volume is already having an impact on a scale beyond that. This is an example of a book coming at the right time and from a place of authority, in this case the critical juncture of sports, history, and cutting-edge medical science, and its influence is likely to be felt on a profound level for years to come.

I have been a boxing fan for more than a decade and it is unlikely I will ever stop watching and supporting it, despite the violence and the risk for its participants. As fight fans, we live in a constant dichotomy, a never-ending conflict. Like Schulberg, as much as I love boxing, I hate it. I love that boxing presents an opportunity, unlike any other, for men and women to demonstrate their courage and skill, but I hate the price many pay for their ring achievements. Thankfully, boxing now has a valuable resource in Damage, a book that serves the sport well as it helps us better understand its dangers and the need to, somehow, make it less dangerous. — Jamie Rebner