rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

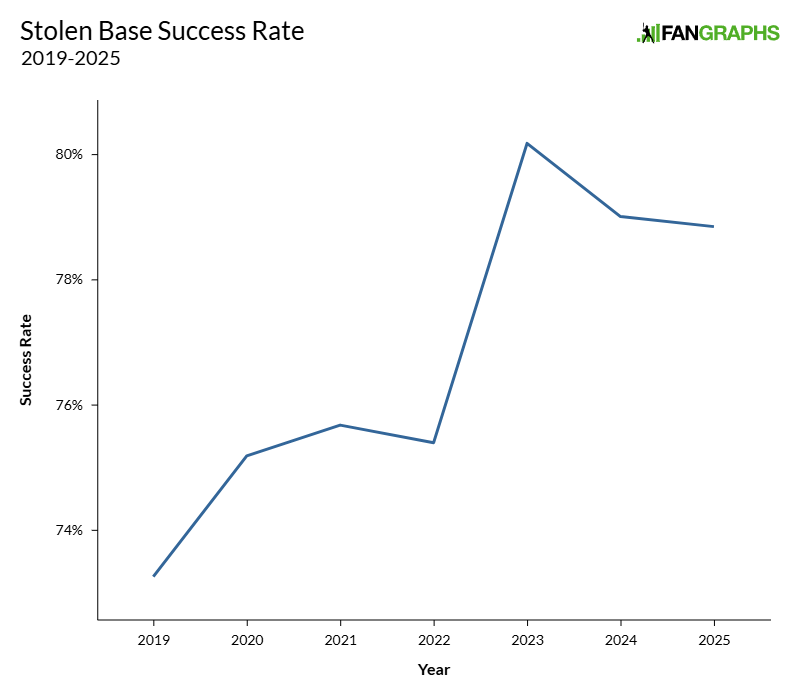

This season is the third since the implementation of a spate of significant rule changes across the majors. Along with a pitch clock and limits on defensive positioning, a limit on disengagements (read: pickoff throws plus idle standing around) combined with slightly larger bases gave runners a collective green light. With fewer throws to first, bigger targets to slide into, and more predictable pitcher deliveries thanks to the clock, stealing a base got much easier overnight. In 2022, the last year of the old rules, the majors saw 2,486 steals across the entire season. In 2024, that number surged to 3,617 steals. Even better from an offensive perspective, the stolen base success rate jumped from 75.4% to 79% over that span.

The first year of the new rules was all about experimentation. Some players ran wild – Ronald Acuña Jr. more or less took off every time he could. Meanwhile, the Giants stole just 57 bases as a team, fewer thefts than the previous year, when those steal-boosting rules weren’t yet in effect. None of that seems particularly surprising to me; when new rules of this import are added to the game, every team will scramble to figure out how to change their own behavior to benefit. There were a ton of moving parts, and many teams took a simple approach: keep stealing more and more until it starts to fail.

The 2024 season was the year of the defensive reaction. Teams attempted 209 more steals in 2024 than they did in 2023, but only succeeded on 114 of those extra steals. The aggregate effect was a lower success rate on marginally more attempts. Catcher pop times improved, pitchers threw over more often, and defenses were more attentive to baserunners in general. That brings us to 2025, and in the early going, it looks like the baserunners are continuing to push the envelope:

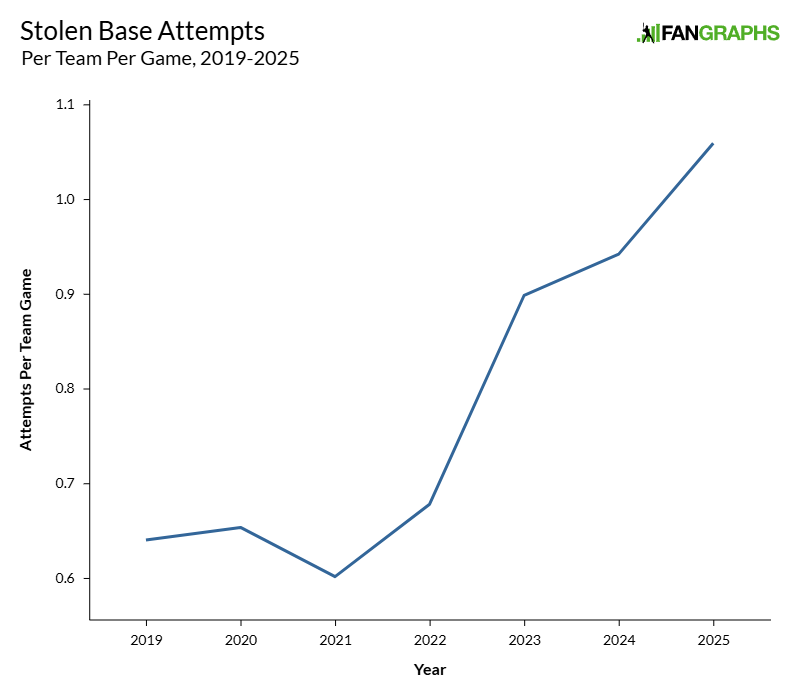

My preferred way of looking at how often teams are stealing is stolen base attempts per team per game. That’s exactly how I picture the proclivity to run in my head, and it adjusts for short seasons and incomplete seasons equally well. In 2023 and 2024, we saw roughly equal stolen base attempts; this season represents a step change in the early going. Stolen base attempts are up twice as much, year over year, as they were last year, and runners are succeeding at the same clip nonetheless, a 78.8% success rate after 2024’s 79.0%:

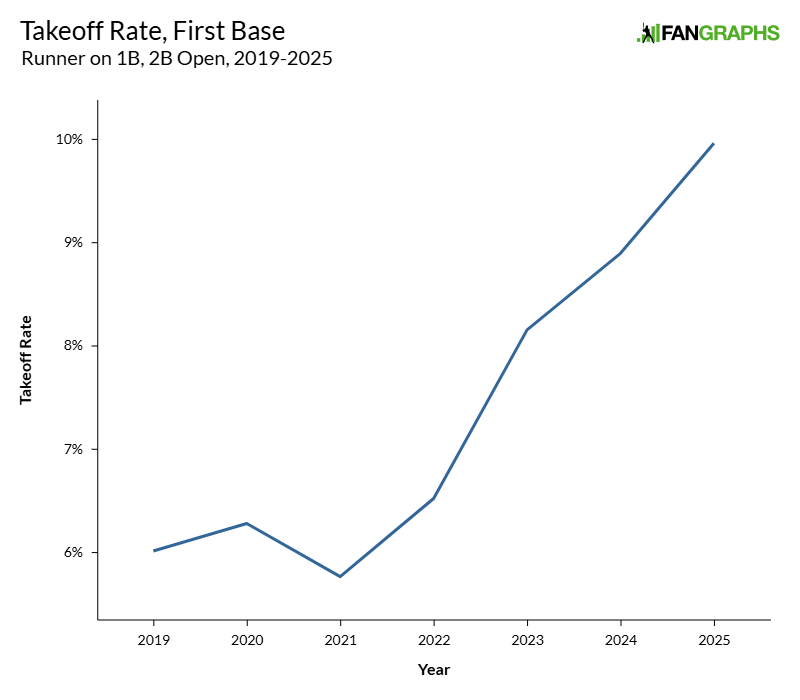

Okay, I fibbed a little. Stolen base attempts per team per game is pretty good, but we can actually do a bit better. That metric uses “games” as a denominator, but that’s not quite right. A league with only home runs and strikeouts wouldn’t have any steals regardless of how fast the runners were. A league where a runner started on first base every inning would have many more stolen base attempts. Opportunity matters. For a team to attempt a steal, they need a runner on base, and most frequently a runner on first base with no one on second.

This data isn’t perfect, because it’s scraped from a messy database and I’m absolutely sure that a rogue weird play or two snuck in. It’s also not an exact encapsulation of “stolen base opportunities” for several reasons. Runner on first down 11 in the bottom of the eighth? You’re probably not stealing, but I’m counting it. Double steals? Completely ignored. Steals of third? We’ll get to those later, but I’m ignoring them for this. With all that in mind, though, this graph tells you that baserunners are taking greater liberties with every passing year:

The “rate” in question is attempts to steal second per time with a runner on first but not second. I like to call it “takeoff rate” – how often a runner with a chance to steal gives it a try. I think that the exact numbers might be off by as much as a tenth of a percentage point, but that doesn’t really matter. The trend is large and unmistakable.

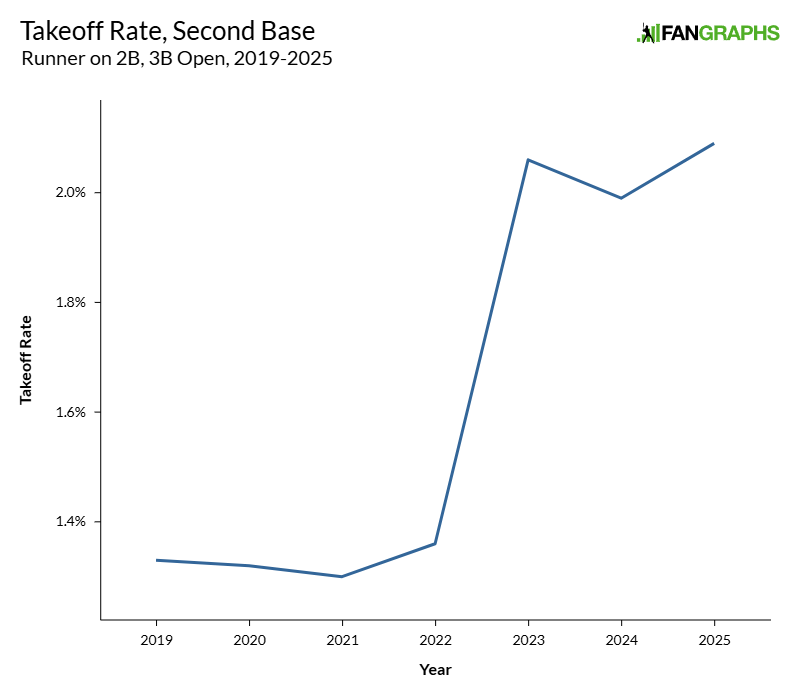

The new rules have also made stealing third base easier. In 2023, runners stole third a whopping 510 times and were successful at a ludicrous 84.3% clip. But as Leo Morgenstern pointed out, that trend didn’t continue last year. By season’s end, teams had attempted 38 fewer steals of third, and succeeded 44 fewer times. That’s not a huge change, but it at least suggests that stealing third might not be the cakewalk it seemed like in 2023.

I wanted to check in on 2025, so I again created a set of opportunities to steal third base. I made mine fairly simple – I counted every time there was a runner on second base but not on third and made that the denominator. Every steal that lead runner attempted went into the numerator – double steal, delayed steal, they all count the same. Maybe there’s not much to see here:

Then again, steals of third aren’t working as well as they used to. Their success rate has dropped from 84.3% in 2023 to 82.2% in 2024 to 80.5% so far this year. I’m sympathetic to the idea that defenders just needed some time to adjust to defending this play. Stealing second is something that features heavily in every game that catchers have played more or less since kids started pitching in little league. Stealing third? It’s a lot less common, and thus less drilled.

Teams attempt to steal third nearly twice as often as they did before the rule changes; maybe defenders just needed a season or two to adjust to the play in spring training. Third basemen, in particular, have a tough job with a runner on second, as they have to make themselves available for a throw while still playing defense. I’d hardly be shocked if the real change in steals of third is fewer non-competitive attempts, where no defender covers the bag and the catcher doesn’t even throw.

So what’s the future of the stolen base in the majors? I don’t think we’ve figured it out yet. Teams are running more frequently with each passing year, but they’re succeeding less frequently as defenders adjust to the new rules of the game. Offenses are still adding plenty of value on the basepaths – in keeping with what math tells us about the optimal stolen base success rate – and they’re particularly doing so at second base now that defenses are improving at covering third. If there’s a runner on first with a free base ahead of him, you can expect to see a stolen base attempt about 10% of the time, up from about 6% of the time under the old rules. That’s a huge change, and one that’s unlikely to revert to the previous era of basestealing any time soon.

None of this is static, of course, which is part of the problem with early-season baseball analysis. The Brewers have stolen more bases than the bottom four teams in baseball combined; we’ve never seen a full season disparity that large. The sample sizes are still tiny, with less than a month in the books, and one marauding (or cowardly) week can still skew the numbers. Chandler Simpson’s call-up alone could change the pace of stolen base attempts; the man swiped triple digit bags in the minors last year. But that doesn’t mean we can’t check in, and so far this year, teams are keeping their feet on the gas pedal and charging ahead. Sorry, catchers – looks like you have more work to do.

Statistics current through games of April 21.