Until December of 1952, some eighteen years after he had embarked on what would eventually be an all-time great pro career, Archie Moore was part of that long list of over-accomplished African-American boxers who had never competed for a world title. By that time “The Old Mongoose” had 160 fights, nearly a hundred knockouts, not to mention victories over several future Hall of Famers but, like many other members of the renowned “Murderer’s Row” gang, Archie had little to show for his accomplishments besides a glossy record.

But unlike some of his black counterparts, Moore persevered. Never quitting his day job, while surviving both acute appendicitis and a perforated ulcer that almost killed him, he soldiered on with unbreakable will and astonishing patience. He was 36-years-old when he finally received his first title shot against Joey Maxim, outlasting the likes of Holman Williams and Charley Burley who each retired by the ages of 35 and 33, respectively. Moore made the most of his breakthrough opportunity, scoring two knockdowns and dominating Maxim en route to a fifteen round unanimous decision and the light heavyweight championship of the world.

Contrary to Jack Johnson, who was widely criticized for not giving title shots to turn-of-the-century black contenders after he crossed the infamous “color line,” Moore gave back. He was less than two years into his reign when he gave a chance to Harold Johnson, an accomplished pugilist and clearly one of the more dangerous contenders in the division. In fact, Johnson held a win over Archie from their four fight series which had been contested when both were spinning their wheels in a seemingly never-ending road to a title shot.

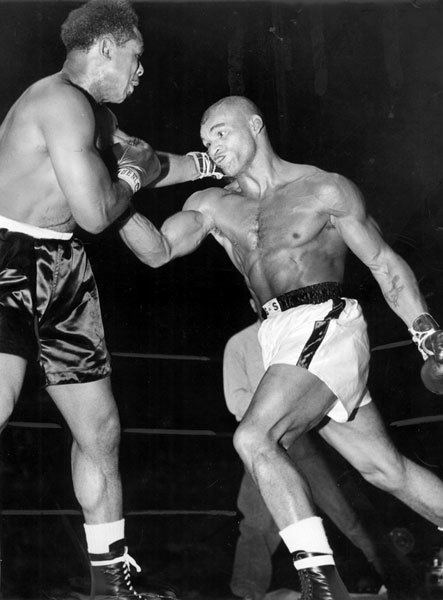

While not as experienced as Moore was when he received his first title shot, Johnson had solid credentials, not to mention 52 pro tilts to his credit. And not only had Johnson defeated Moore previously, but the Philadelphia-based contender also held victories over future Hall of Famers Ezzard Charles and Jimmy Bivins and was ten years Moore’s junior. A brilliant counter-puncher with an educated jab, Johnson had made it difficult for Moore to close the distance in their previous meetings, but if there was one advantage Archie held in those four bouts, it was his ability to close stronger as he consistently hurt or downed Johnson in the late rounds. Given that Johnson was facing the fifteen round distance for the first time, it was clear the challenger had his work cut out for him.

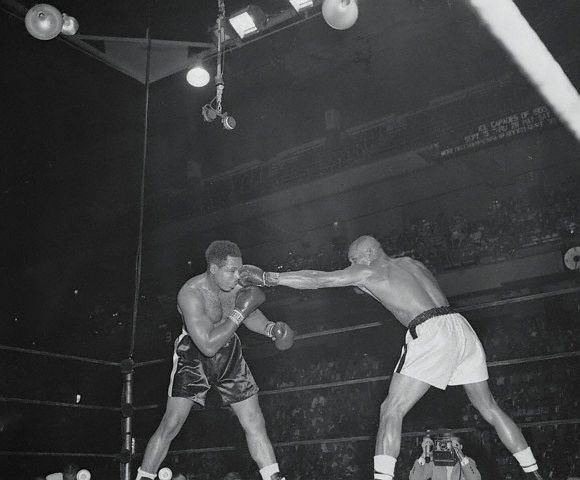

The first half of Moore vs Johnson part five played out in a style rather similar to their previous bouts. Johnson kept Moore at a distance by firing his jab, tying him up, and counter-punching effectively. Some adept footwork also helped the challenger to keep the proceedings where he wanted them, in the center of the ring. But Moore got through in round seven, hurting Johnson with a right hand and tattooing the younger man to the rib cage. Moore, who had his sights set on heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano going into this fight, appeared to breathe a sigh of relief at the bell and he raised his hand as he strode back to his corner.

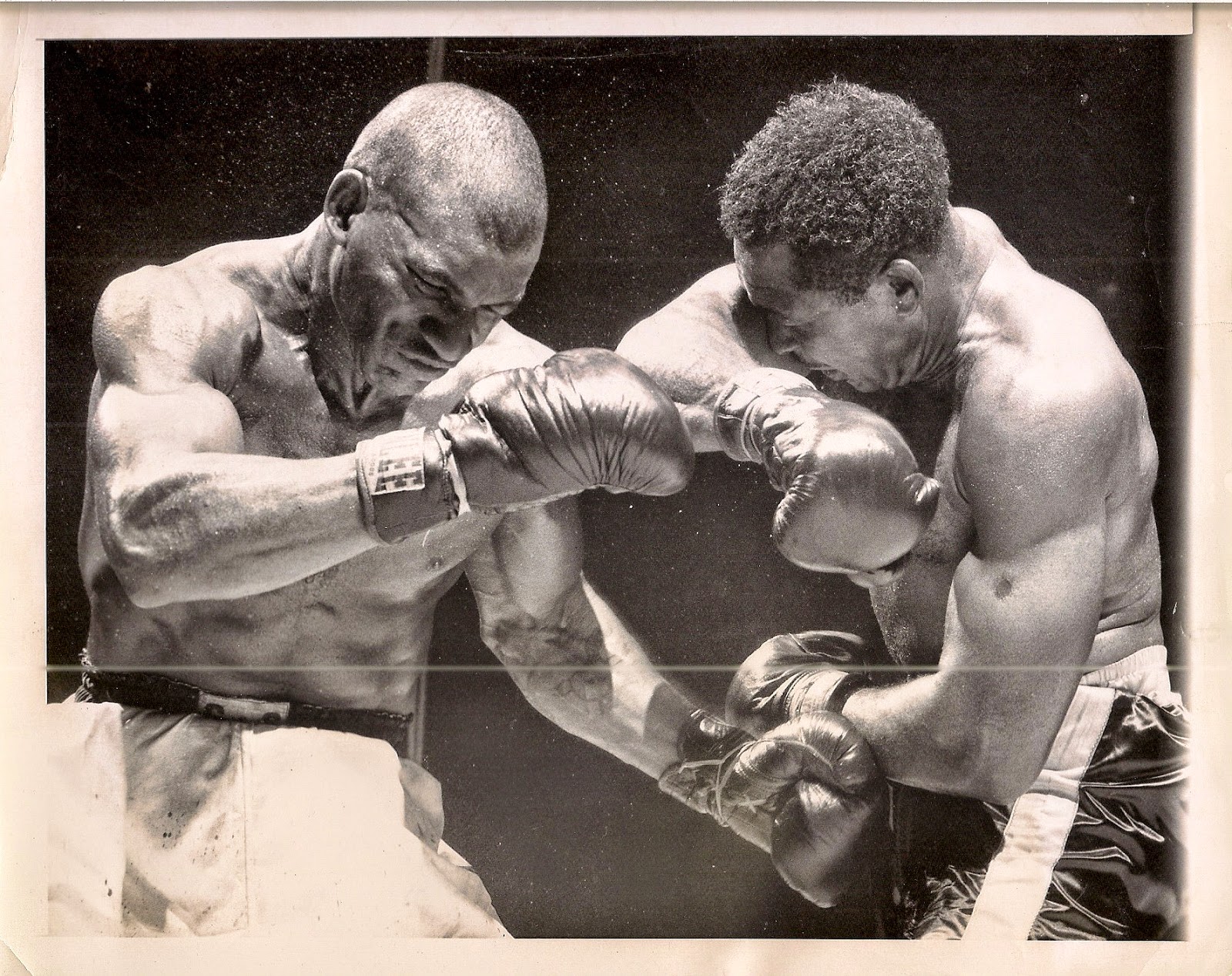

And indeed, from here on, Moore took over. Stronger and more physical in the trenches, he negated the challenger’s jab by firing his right over the top. But just when “The Old Mongoose” appeared on the verge of closing the curtains on Johnson, the boxer they called “Hercules” struck in round ten with a right hand behind the ear that put Moore on the deck. Archie rose and appeared unhurt, but the bell rang before Johnson had a chance to test those waters. The champion later claimed that while Ezzard Charles had knocked him out with a similarly placed blow in 1948, “this one [by Johnson] didn’t even hurt a little,” and sure enough Archie was right back on his man in round eleven.

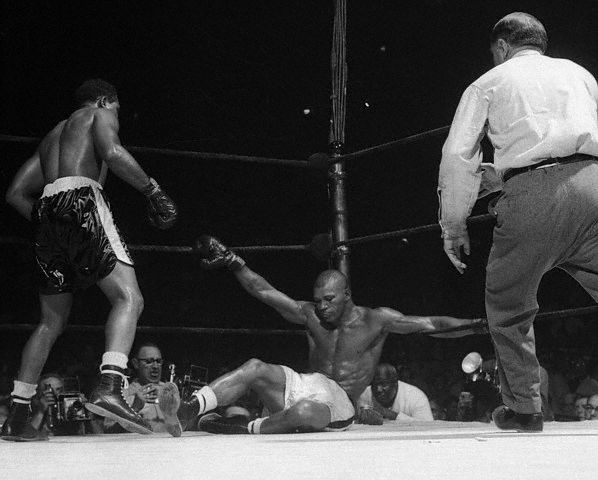

In the thirteenth the champion hurt Johnson with a crushing right cross over the jab, staggering the challenger who was subsequently saved by the bell. “The Old Mongoose” sensed the end was near and between rounds told his manager Charlie Johnston: “I’ll knock him out in this round.” The bell rang and Johnson was clearly on shaky legs coming out of his corner. Thirty seconds later Moore landed another vicious right. Sensing Johnson was ready to go, the champion unloaded a fusillade of uppercuts, left hooks and right hands to score his first knockdown of the fight.

Referee Ruby Goldstein let the match continue once Johnson pulled himself to his feet, but the challenger clearly didn’t have his legs under him as Moore went in for the kill. A few more solid punches had Johnson looking like a rag doll along the ropes before Goldstein stepped in and declared Moore the victor.

Looking back on their five fight series, it’s worth noting that Archie Moore and Harold Johnson transcended an era of boxing that was, at best, indifferent to their success. Both were among the earliest inductees into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, and both are among the all-time greats at 175 pounds. Together, they gave us one of the best rivalries in light heavyweight history; boxer against puncher, youth against age, craft against wisdom. — Alden Chodash