“To dare is to lose one’s footing momentarily.To not dare is to lose oneself.” — Soren Kierkegaard

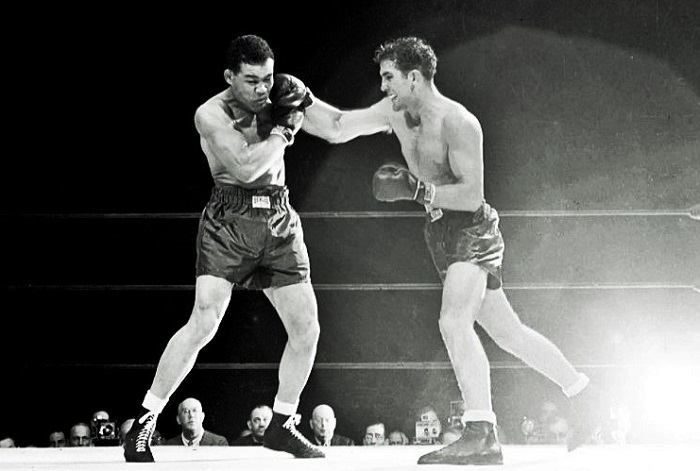

Over the decades we have been told time and again how the great Billy Conn was foolish to go for the knockout against Joe Louis in round thirteen of their classic 1941 encounter for the heavyweight championship of the world. It is one of boxing’s most famous platitudes and it is rare to find a dissenting opinion. Some even called Billy’s decision to go for the kill downright stupid, an opinion given credence by Conn himself in his famous post-fight comments. “I lost my head and a million bucks,” he said in his dressing room shortly after the legendary duel. Seconds later he was asked why he went for the knockout, the question prompting the immortal line: “What’s the use of being Irish if you can’t be thick?”

Billy Conn is without question one of the greatest light heavyweights who ever lived; pound-for-pound, he will forever be one of the most skilled and talented boxers of his time. But his achievements have been overshadowed by the legend of that first defeat to “The Brown Bomber.” And the opinion that “The Pittsburgh Kid” made a severe error in judgment has been regurgitated so many times over the years that nobody even questions the logic of what they are expected to swallow, each generation taking it as the unassailable truth and the story of the fight.

But is it?

Every sport has its risks. The results of taking these risks are what determine if history remembers it as a wise move or a foolish one. The first thing to judge must be the risk versus reward ratio, and the evidence that was taken into consideration before accepting the challenge inherent in that risk.

When Billy Conn answered the bell for that fateful thirteenth round, the facts and evidence were these:

1. Conn could hurt Louis and had badly staggered him more than once.2. Louis had not been able to hurt Conn to any appreciable degree.3. Conn was out-boxing and out-punching Louis, often beginning and always ending every exchange.

Was Louis still a danger to stop Billy? Of course he was. The champion, one of the greatest punchers in pugilistic history, was always a danger to stop anyone. And indeed the “smart” move would have been for Conn to keep out-boxing the champion until the final bell and be happy with winning the decision. But does that automatically make his decision to go for the kill “dumb”?

Again, not if the evidence of the moment is considered. And if Billy had succeeded in stopping Louis it is a certainty that historians would be talking about Conn’s brilliant game plan of softening Joe up for twelve stanzas before going for the kill in the championship rounds.

Here is something to consider: if Sonny Liston had done as most expected and knocked out Cassius Clay in their monumental 1964 bout, the press, after crowing happily that “The Louisville Lip” had finally been buttoned, would have doubtless taken turns lambasting Angelo Dundee for allowing his promising but still developing prospect to go in against the most destructive fighter on the planet. “What were they thinking?” they would have shouted. “He wasn’t ready!”

Exhibits A through Z would have been his previous two bouts, the first against smallish Doug Jones, in which he struggled mightily and lost some luster, and the second versus Henry Cooper, in which he was dropped and badly hurt by Cooper’s left hook (which, they would have acerbically pointed out, was Liston’s best punch and thrown with much more destructive force from the 215 pound champion than by the thirty pounds lighter Cooper).

But the future Muhammad Ali won the bout, so he, Dundee, and everyone involved were “brilliant” and knew what they were doing all along. Pass the cigars and sing praises to the stellar game plan. He would be given similar praise a decade later after seemingly tempting suicide with George Foreman by fighting off the ropes against the thunderous-punching champion, only to tire the big Texan out and stop him in eight.

Is it not conceivable that we would be singing similar praises in the direction of Billy Conn’s legacy had his risk paid off and he won the heavyweight championship of the world on that legendary New York City night in 1941?

Going for the kill against a tiring and previously wounded Joe Louis who had yet to hurt you; a risky move? Of course. Every worthy achievement involves risk.

But a “stupid” one? No. — Douglas Cavanaugh