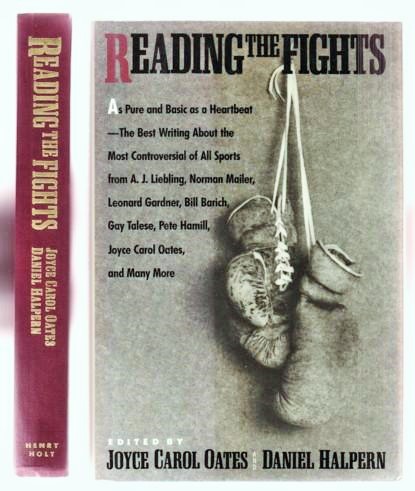

At first glance, Reading the Fights is a compendium of insightful essays which alternate between examining the responses boxing evokes and bringing to life stories of its past, thus providing a sweeping panoramic of what the sport is all about. But upon closer inspection, the reader perceives a purposeful structure in how Joyce Carol Oates and Daniel Halpern arranged their selection of articles. Together the pieces read as a multi-voiced conversation exploring the reasons for both the repulsion and the allure boxing generates, so that the book—just like a good old-fashioned fight—is itself the narration of a conflict.

This multi-generational debate in which fans, regulators, promoters, fighters, media types and concerned pundits all take part, focuses on different topics at different times, but its most significant theme takes aim at the very existence of pugilism. An anthropic theory of the existence of boxing would postulate that it exists because there are fighters who practice it and there are observers who contemplate it, and therein lies the biggest conflict of all. How is it that rational, intelligent and sensible beings—meaning the bulk of the fighters, trainers, businessmen, and even writers and fans for whom boxing is so consequential–how can these people not only tolerate, but actually enjoy and even love, a sport which so many detractors consider degrading at best, and barbaric at worst?

Even with this query in mind, it will be difficult for most fight fans to relate to the opening couple of essays, which dissect in almost grotesque manner everything that is wrong with boxing. And make no mistake, there is much that is rotten about the fight game, and such has always been the case. Though let’s not forget that professional prizefighting—under different protocols and in different times—has offered sustenance and hope to those on the fringes of society: slaves-turned-Roman gladiators, slick vaudeville entertainers, uneducated brutes, former convicts, sleazy businessmen, and worse. With so many of its participating cast walking the fine line between what’s legal and what’s not, it’s not surprising that through its long history boxing has always been accompanied by corruption, incompetence and controversy, and that’s before turning our attention to the scores of ring deaths over which the fight game has presided.

What is surprising, even after hearing everything the detractors and disenchanted have to say about the evils of pugilism, is that people continue to derive from it not only entertainment and pleasure, but also—in those rare, best moments the sport has to offer—glimpses of the kind of beauty that only a combination of athletic excellence and a cunning intellect can produce. It can be argued that athletic beauty reaches an apex in boxing that is not to be seen anywhere else in sports.

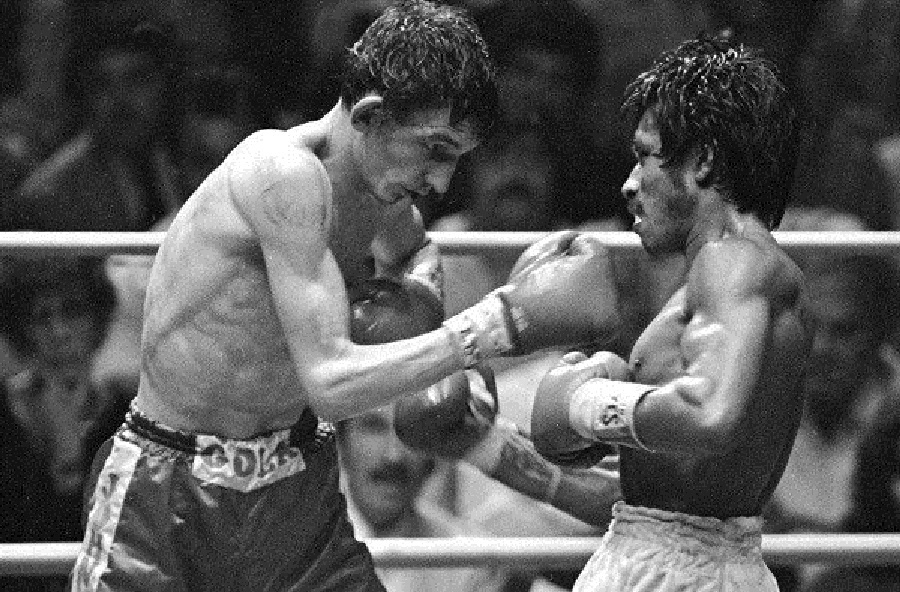

This could explain why devotees of the fights suffer like no other brand of sports fanatic while watching their preferred pugilist confront insurmountable adversity. It also explains the almost unparalleled level of elation felt by aficionados who witness an outstanding boxing contest. Consider, for instance, the fascination of venerable scribe Norman Mailer for Muhammad Ali, in his grandiosely-written, almost hagiographic account of the first Ali vs Frazier match. If you didn’t know who Ali or Frazier were, you would think Mailer was writing about a clash between gods. Or check out Leonard Gardner’s piece on the first fight between Roberto Duran and Sugar Ray Leonard, in which Gardner, writing with a child-like sense of wonder, follows Roberto and his posse around Montreal prior to the monumental clash.

But Reading the Fights also presents us with a fair dose of heartbreak. In his superb “Onward Virgin Soldier,” Hugh McIlvanney tells the story of Welsh prizefighter Johnny Owen and his unlikely rise through the bantamweight ranks. His fragile frame and humble origins notwithstanding, Owen challenged feared champion Lupe Pintor, in what would prove to be a fatal match. After a gallant struggle, the Welshman lapsed into a coma and never regained consciousness.

In “The Loser,” Gay Talese profiles Floyd Patterson who, tortured by shame, hid behind his brother’s name after suffering a humiliating second knockout loss to Sonny Liston. The ending of McIlvanney’s piece, and Talese’s portrayal of Patterson’s internal conflict, are easily the two most humbling moments to be found in this collection, and they are invaluable reminders of the humanity surrounding the fight game.

George Plimpton’s “Three with Moore” provides both humour and a reliable measure of the distance between spectators and the practitioners of boxing as Plimpton documents what it’s like for an everyman to spar three rounds with light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore. The author’s scrawny and anti-athletic physical disposition only makes the task seem all that more hopeless, and as his anxiety about the upcoming match grows, so does the fun in reading about it. Still, it is Plimpton’s narration of the encounter itself that brings into perspective the magnitude of the abyss that separates ordinary men from ring champions.

The closing essay is Oates’ iconic “On Boxing.” In it, Oates recognizes that no other sport takes its history as seriously as boxing. Both those active in the brutal game, and those who follow it religiously, look over their shoulders to keep the past as a point of reference in assessing those toiling in the present. But this point is important to keep in mind as readers make their way through this collection for yet another reason. Many of the references these essays make to the controversies of the sport are placed firmly in time: Mancini vs Duk-Koo Kim, Griffith vs Paret, Owen vs Pintor. It’s remarkable that the mere mention of these pairings immediately brings to mind a sense of recognition and acknowledgment of boxing’s tragic cost.

But along with this acknowledgment comes remembrance. We speak of transcendent fights as monumental and heroic deeds, just as we refer to the sport’s darkest moments as real tragedies and there’s a self-reinforcing mechanism at work here. We are drawn to pugilism’s past because we care about both its present form and its future, because we remember the heights to which it can take us. Reading the Fights helps us remember and revere iconic events in pugilistic history, but its greatest value lies in its exposition of boxing’s innate and unrivaled ability to both attract and repulse.

Perhaps few statements capture the duality of boxing fans’ relationship with the sport as effectively as Oates’ pronouncement: “If the boxing ring is an altar, it is not an altar of sacrifice solely but one of consecration and redemption. Sometimes.” – Rafael García