It’s 1985 and everyone south of the border already knows who the next great Mexican boxer will be. The only problem is pretty much no one north of the border does.

The 70s and early 80s were vintage years for Mexican fight fans with Carlos Zarate, Ruben Olivares, Miguel Canto, Lupe Pintor, Pipino Cuevas, and Salvador Sanchez all establishing themselves as dominant champions. But their time had come and gone and the question now was who would rise up to carry on the legacy.

At this point a young Julio Cesar Chavez was the winner of 46 straight and some were already comparing him favorably to the greats of the past, but the vast majority of those bouts had taken place in Sinaloa and Tijuana. His recent wins over faded competition at the Forum in Inglewood or the Olympic Auditorium in L.A. had generated no buzz. Even his title-winning effort, a sixth-round stoppage of Mario Martinez had sparked little interest.

But Mort Sharnik, boxing programmer at CBS television, recognized Chavez was a special talent and he wanted to be the first to bring him to the attention of mainstream fight fans. He talked to Chavez’s promoter, Don King, who set up a match with former champion Roger Mayweather. Originally, Chavez vs Mayweather was to take place in a bullring in Tijuana, an idea Sharnik loved, but soon enough the novel idea was quashed. “What I hear,” said a disappointed Sharnik, “King thought they were talking dollars when they were talking pesos.”

So instead the match moved to The Riviera in Las Vegas. And while Mayweather remained a potentially dangerous foe, the idea behind the fight was to showcase Chavez. What a showcase it was.

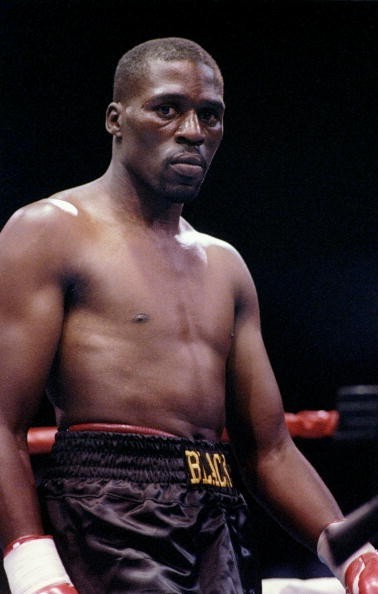

Midway through round one commentator Tim Ryan remarked how “boxing experts have already compared the 22-year-old champion to the likes of Ruben Olivares, Salvador Sanchez, Carlos Zarate.” Moments later, as if on cue, Mayweather, not Chavez, got home a thudding right hand. In fact, the opening round clearly belonged to Mayweather as he boxed effectively, landing jabs and right hands while Chavez stalked and did little more.

However, the start of round two saw a more aggressive Chavez shortening the distance. Mayweather responded to the pressure, snapping home quick shots including a sharp right which appeared to briefly stun the champion. But Chavez kept coming and was now winging his own right with abandon, countering Mayweather’s jab.

Just over a minute into the round, the Mexican connected with two powerful rights; the first one buckled Mayweather’s legs and the second one put him down, though referee Richard Steele blew the call, ruling it a slip. No matter. The future “El César del Boxeo“ calmly walked Mayweather down, driving powerful punches to his ribs before landing three rights upstairs, the last catching the challenger wide open, viciously snapping his head around and dropping him again.

Mayweather bravely got to his feet but was in bad shape. Trying to clinch, he reeled from the fury of Chavez’s attack, stumbling to the canvas a third time, his legs gone. No sooner was he upright than Chavez was on top of him, throwing wild right hands. Unable to hold and subdue his stronger opponent, Mayweather backpedaled about the ring on unsteady pins, but the champion would not be denied. A crushing right followed by a left put Mayweather down yet again. Game to the end, Mayweather climbed to his feet but Steele had seen enough and called a halt.

“This young man is for real!” cried Ryan as Chavez and his handlers celebrated. Indeed, he was. For network television debuts, this was as good as it gets, as it heralded the arrival of The Age of Chavez and the start of a decade of high-profile bouts for the man many believe is the greatest Mexican boxer of all time. — Robert Portis