rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

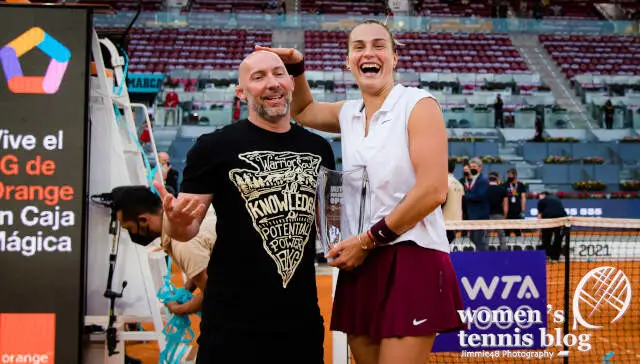

Holding three Grand Slam titles from hard-court tournaments, Roland Garros has long eluded Aryna Sabalenka. The world number one has historically struggled on clay, but on Thursday, she turned a corner, defeating four-time French Open champion Iga Swiatek to reach her first final in Paris. Key to her rise has been work with performance coach Jason Stacy, who has helped her find peace when pushed to physical and mental discomfort.

In an exclusive interview with Women’s Tennis Blog, the American detailed how his background in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu brings a unique perspective to the tennis star’s athletic development. To be clear, Sabalenka is not learning these moves to fight. When Women’s Tennis Blog asked her about the martial arts inspired training, she emphasized that it was about core strength and not combat: “The moment I realize how strong I am and I can do something, I’ll probably go really crazy on my team. I think they don’t want that, so they’re not really letting me do that. We will stick to soccer and these games.”

Stacy’s work began with a fundamental objective: fostering a deeper connection between the athlete and her own body. “Over the years, we’ve been working specifically on how to get her this awareness of her body,” he explained.

“First, we built up that awareness of the power in her body, and from there was the work on control.” To achieve this, Stacy incorporated exercises from combat sports that may seem unconventional in tennis: “We did various crawling drills, a lot of positions where she had never been, so she had to feel where her body was and have this awareness.” Once this foundation was established, he gradually introduced complexity: “Then I would add different loads, different positions, or go to and from different angles.”

As part of building bodily awareness and revealing again the martial arts background, Stacy champions barefoot training. He told Women’s Tennis Blog, “If we’re not on the court, we’re barefoot: no socks, no shoes, jogging, walking, post-match, pre-match, doing various exercises.” The benefits are far-reaching: “From good sensory input, good control, good strength, it goes all the way up from your feet to your pelvic floor and your core.”

While acknowledging the role of foot position in generating power, Stacy underscores that true strength and control emanate from the body’s center. “Most of the power, control, and the coordination come from your center. Everything’s about your center,” he stresses. Without a stable and controlled core, external movements will lack the power needed on court. “If your center is not stable, not controlled, or it doesn’t have the right of relaxation and tension and doesn’t have the right awareness and control, whatever you have coming from the ground up is not going to translate out of your arm or your racquet.”

Compared to many of the women she faces on tour, strength and power come easily to the daughter of an accomplished ice hockey player. The performance coach’s job is to help her effectively harness that gift even when forced into uncomfortable positions, such as on a slippery clay court. With a properly trained core he says, “Instead of relying on the ground and having to push off the ground, she can actually have that strength and coordination, no matter if she’s on balance or off balance.”

Stacy, who has trained athletes from the full spectrum of competitions and disciplines, broadly applies a strategic framework derived from combat sports: Defend, Control, Attack. This isn’t just about aggression but a complete cycle of engagement that has guided his approach to the mental aspect of the Belarusian’s game.

“Defend doesn’t mean you’re being defensive necessarily. It means that you’re making sure that you’re not leaving any gaps, that you’re in control of what’s going on.” He clarifies in tennis terms, it’s “not doing something stupid… doing the right thing, getting the ball back.”

Once defense is solid, the focus shifts to control. “Control is internally controlling yourself, trying to apply your strategy. In tennis, for example, it’s finding that rhythm, you’re controlling where the ball is going, you’re controlling your technique. You’re not overhitting. You’re not underhitting, you’re just in that sweet spot.”

The final phase is attack, which emerges from successful control. “If you do it the right way, and you have that control, then you’ll open up the court, then you can attack,” he states. This cyclical nature is key: “Maybe you attack, and they get the ball over. Great! You go back to defense, get back in control, attack again!” This mindset fosters resilience and freedom, allowing athletes to take risks knowing they can reset. “It gives you space and freedom to attack,” Stacy concludes.

This philosophy, deeply intertwined with the body awareness and core strength he cultivates, allows a player to maintain composure and adaptability under pressure. “The better you are in your technique, the better you are at being adaptable and being used to being in these situations that you’re not comfortable,” he notes.

While Stacy works with elite athletes, the principles he champions offer benefits for any woman who might consider adding martial arts to her sports and fitness regimen. A primary benefit he emphasizes is mental strength: “You learn how to manage your emotions a little bit better. Learn how to breathe and be able to step outside of yourself and think a little bit more clearly,” he says this happens as you, “start to learn a bit more about what you’re capable of.” This “zoom in, zoom out” ability is valuable in any endeavor. Aside from the overall well-being and improved confidence, he adds: “You’re gonna have a core like no one else was ever gonna have. Your hips, your core, your pelvic floor, that’s all massive stuff, especially as you get older.”

Stepping into a martial arts gym for the first time can be daunting; however, because of the risk of injury, many combat sports have paradoxically fostered an incredibly loving and caring community. Built on mutual respect, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu gyms in particular are known for their welcoming and friendly attitude towards anyone who walks through the door and wants to learn. As Stacy explained, if you injure your training partner, that’s one less person to train with the next day who can help you improve.

While clay may still not be the hardcourt champ’s favorite surface, Jason Stacy’s training has taught the 27-year-old Sabalenka composure under pressure and in the precarious balance of a sliding surface. Her comfort on clay will be tested Saturday in the Roland Garros final against world number two Coco Gauff.

![Implementing & Innovating – Steve Anschutz, Concordia University – Wisconsin [Coaches Podcast] Implementing & Innovating – Steve Anschutz, Concordia University – Wisconsin [Coaches Podcast]](https://i2.wp.com/wearecollegetennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Coaches-Podcast-Cover-Steve-Anschutz.jpg?w=350&resize=350,250&ssl=1)