The question is posed: who was the first Black man to win a world boxing championship? And here are the likely replies: Jack Johnson? Joe Gans? While incorrect, these answers reflect the fact that, for reasons unknown, Johnson and Gans enjoy greater renown than the man who in fact first broke the color barrier in boxing more than a century ago. In fact, the first Black man to be a recognized as a world champion, was not Johnson or Gans, but one George Dixon from Nova Scotia, Canada, a true all-time great who was better known in some circles as “Little Chocolate.”

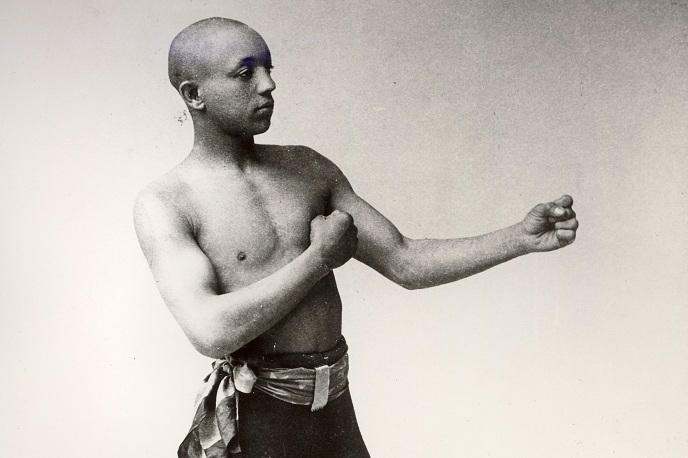

Born in the historic settlement of Black loyalists and freed slaves near Halifax called Campbell Road, later to be named Africville, Dixon first became interested in boxing when assisting a photographer who took publicity shots for various pugilists and became fascinated with the stories he heard from various prizefighters. Soon enough, young George was stepping through the ropes to try his luck and see what kind of money he could make slinging leather. Dixon stood 5’3” and weighed all of 87 pounds when he began competing at the tender age of sixteen. He won his first bout in Halifax in 1886 and the following year left Nova Scotia for Boston, Massachusetts, hoping for glory and riches. He found both, but it all ended up being a bit more than he could handle.

Once in Boston, it didn’t take long for Dixon to establish himself as a boxer of exceptional talent. Just three years after leaving Nova Scotia he claimed the featherweight championship of the world, and the following year he annexed the bantamweight title. While champion, Dixon, despite the fact he was a victim of racial discrimination on numerous occasions, gained wide recognition as one of the finest boxers in the world, bar none.

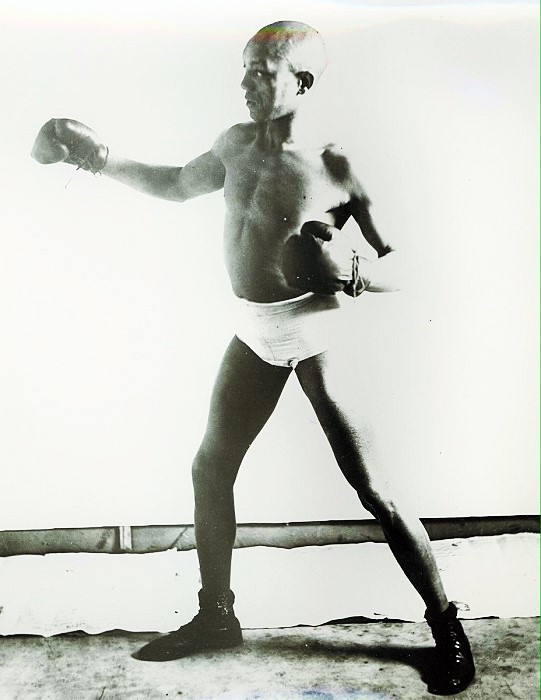

Sam Austin, editor of one of the more popular boxing magazines of the time, Police Gazette, rated Dixon as “a fighter without flaw,” and in the June 27, 1900 edition of the same magazine there was featured a photograph captioned, “Characteristic fighting pose of the Greatest Pugilist the World ever saw.” No less an authority than Nat Fleischer, founder of The Ring magazine, described him as “a marvel of cleverness … fast, tricky, combative, canny, courageous, a master in every respect of the art of self-defense, a great ring general.” Both Fleischer and renowned historian Charley Rose ranked “Little Chocolate” as the greatest bantamweight of all-time.

A complete boxer, Dixon possessed excellent power in both hands and the ability to both box with technical aplomb, or chase and batter his opponent into submission. His superior quickness and excellent footwork allowed him to spring at opponents like a cat behind a sharp left jab and a jarring right to the body. One of his favored tactics was to feint an opponent out of position before rushing him to the ropes and scoring with hard body blows.

In addition to being one of the first and finest technical boxers, Dixon is credited for a number of important innovations, and for being a huge influence on many of the greats who followed, including Jack Johnson and Joe Gans. Dixon invented the common training practice of shadow boxing and he is regarded as the first professional boxer of note to work with a punching bag suspended by a chain or rope. His understanding of the correct stance and footwork, as well as how to combine telling blows from both fists, was all ahead of its time. He remains, arguably, the fight game’s first true master.

As remarkable as Dixon’s career was, his official boxing record does not accurately reflect his achievements. While it gives Dixon credit for 151 bouts, his manager claimed he fought more than eight hundred. If true, this would make him the most active boxer in history. Additionally, many of his official losses were no doubt the result of racial prejudice. On numerous occasions Dixon had to contend with racist ring officials and hostile audiences.

Historian Tracy Callis has stated that Dixon “won nearly 90 percent of the draws and losses on his record but due to various reasons he did not get credit …” As further evidence, the Sept. 30, 1893 Police Gazette states that “nearly every time Dixon has been pitted against a champion, no matter whether foreign or native, the majority has named Dixon the loser, probably through prejudice, owing to his color, yet he has won.” For example, his bout with the great Abe Attell in 1901 stands as a draw on the official records, while newspaper accounts depict a contest which Dixon clearly got the better of.

But despite such difficulties, Dixon enjoyed one of the longest and most successful championship runs in boxing history. He engaged in at least 23 world title bouts, a record that remained unbroken until the reign of Joe Louis, more than forty years later. As a result, Dixon achieved the kind of renown a little kid growing up in Nova Scotia could have only dreamed of.

In fact, by the time of that showdown with Attell, “Little Chocolate” was on the downside of his career and it wasn’t entirely because of the passage of time. Amazingly, Dixon had managed to maintain his hectic fight schedule and long reign while rarely resisting temptation, living the high life of a famous champion and celebrity. When George finally retired in 1906, he was an alcoholic and he died less than three years later. Sadder still, at the time of his death he was penniless. It is estimated that Dixon burned through over two hundred thousand dollars while living the high life on the road, millions in today’s dollars. Dixon’s life is both a tragic testament to the widespread racism of times past, as well as a cautionary tale. But transcending both is his superlative boxing skill and ring achievements. — Neil Crane