Katsuhiro Harada surprises me with a question of his own. I’ve spent the last half hour challenging the Tekken development chief to remember the first game’s launch on the original PlayStation over the course of 1995, first in Japan, then in Europe and North America. I’m not used to my interviewees turning the tables on me. I’m meant to be the one asking the questions! But Harada, from behind his trademark sunglasses, has the same curiosity about the much-loved 32-bit generation that I have.

“Do you know how old you were and what you were doing when Virtua Fighter first came out?”

As I often am while playing fighting games, I’m thrown. Sega’s influential Virtua Fighter released in arcades in 1993 before launching on the Saturn a year later. I have a vague memory of playing it round a friend’s house in Streatham, South London, I think in the summer of 1995. I was 13 going on 14, I tell Harada, betraying my veteran status.

Harada wants to know if Virtua Fighter was as big in the west as it was in Japan all those years ago. “Did it really take off or not so much?”

I tell him how Virtua Fighter on the Saturn impressed me, but not as much as Tekken on the PlayStation. It was King’s multi-part chain throw that did it for me, in Tekken 2 I think, although my memory is fuzzy. Yes, Tekken 2 round another friend’s house, this time in Dulwich. Or did I see the chain throw first on telly? GamesMaster, or maybe Bad Influence?

Here’s what I do know: I could not believe my eyes. Here was a fighting game character packed with polygons performing complex throws each with a realistic animation, expertly blended as if drawn on-screen with a fountain pen. I felt, watching the chain throw slowly unfold, as if the developers had made sure every limb moved the way it would, should anyone actually try to pull this off in real life. King ends his bone-crunching deconstruction of his hapless opponent with a flourish: the giant swing. There’s no coming back from that.

All of a sudden Street Fighter 2, with its fantastical fireballs and flaming fists, seemed childish. Like a cartoon. Tekken was grown up, it was cool, and it was in my mate’s house. No need to rinse my pocket money in the arcades of Streatham Hill’s famous post-school haunt, Megabowl. Here, on PS1, my love affair with Tekken could run free.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but Tekken was selling me on PlayStation as much as it was the game itself. The PlayStation’s mainstream success helped drag Tekken out of the hardcore fandom it had enjoyed in arcades and into the big time. If you bought a PlayStation at launch you probably bought Ridge Racer, Namco’s other blockbuster PlayStation port, to play on it. But if you fancied another game a few months down the line, Tekken was your go-to.

The young Harada, having just joined Namco (and long before the acquisition that created the Bandai Namco we know today), didn’t work on those early Tekken PS1 ports. Instead he worked on Tekken’s arcade versions, which always launched first before coming to consoles. Those days, Harada did little else but go to and fro the office and the arcades to check how Tekken was being played out in the wild. He tells me that he’d only spend one day at home for every two months at the office during those early Tekken days. For Harada, Tekken was life. I get the impression it still is, three decades later.

At the time, Harada was a junior member of staff, not the face of Tekken he has become. But still, word of strategy, performance, and the latest cool moves would filter down to street level – and this is why Harada asked me about Virtua Fighter.

“It converted you from arcade to console in a very sort of natural, organic way. I didn’t realise it at the time…”

“It’s not like somebody said, ‘Hey, we want this fighting game because we want to put it up against Virtua Fighter.’ But obviously they must have thought that because if you were in Japan at the time, you saw that being able to play such an amazing game like Virtua Fighter was a technological marvel at home.” Harada smirks. “It was huge,” he adds. “And so it’s hard to think that Sony didn’t notice and, ‘Wow! We would like to have our own kind of title.’ “

Sega, at the time, was doing it all. King of the arcade and console, the business behind Sonic was adept at porting its cutting edge 3D arcade graphics tech to the home. Sony, on the other hand, had no arcade pedigree to draw upon. It entered the console war as a new challenger, and so it needed to buy in the know-how to compete with Sega’s Virtua Racing and Virtua Fighter.

Namco’s Ridge Racer and Tekken, then, became de facto PlayStation exclusives. Sony and Namco’s shared belief that the future of video games depended upon cutting edge 3D graphics in the home fueled a partnership that blossomed as the PlayStation grew in popularity. It was a match made in heaven, and Sony never looked back.

Tekken’s PS1 ports weren’t just technical marvels. Harada remembers Namco spent a great deal of time and energy fleshing the arcade versions out with extra content for PlayStation, where credits weren’t a thing. Namco even stuffed mini-games into the loading screens. Tekken wasn’t just a fighting game, it was a console game that would keep you going for months, perhaps even years. As Tekken evolved over the course of its first three games, so did the idea of a fighting game with a story. “It became a staple of what people expect from a consumer port,” Harada says.

Sony, smelling a hit exclusive, invested heavily in promoting Tekken in the west. It brought its considerable marketing resources to bear on impressionable teens who were looking for something they wouldn’t be ashamed to play on this grown up games machine. “People knew it as Sony’s Tekken,” Harada remembers. “All the effort and funds Sony put into the market was just enormous. So that really helped launch the popularity and recognisable aspect of Tekken around the world.”

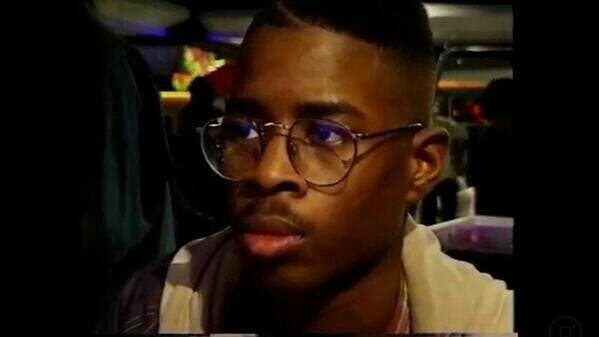

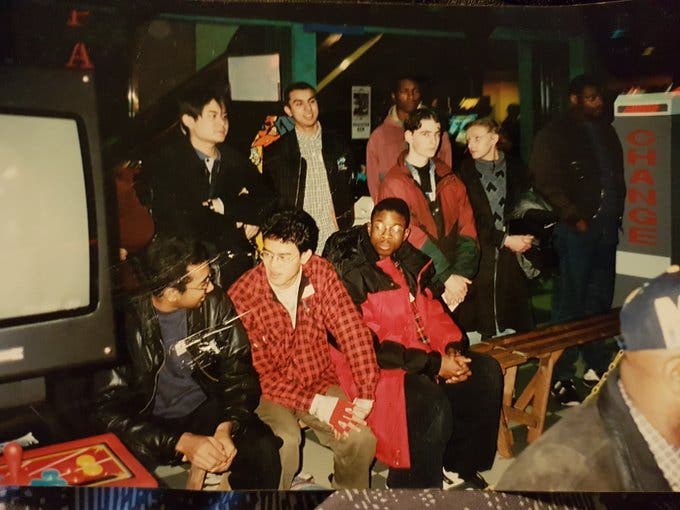

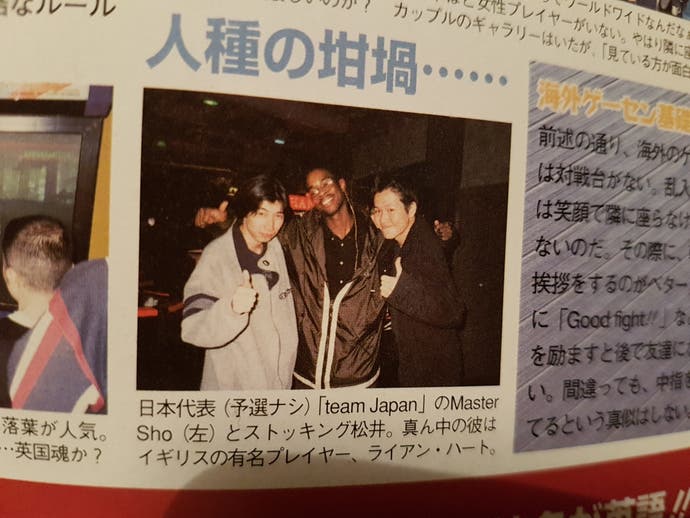

Ryan Hart is perhaps the world’s most famous Tekken player. The ‘Prodigal Son’ holds a string of fighting game-related Guinness World Records and is a two-time winner of the Evolution Championship Series. He found his first Tekken tournament success at the Tekken 2 UK National tournament, where he placed fourth with King.

Hart didn’t buy a PlayStation, he won one alongside Ridge Racer at a fighting game event. “I was not doing too good in life and I didn’t have a lot of money,” he says. “And winning the PlayStation was a massive thing at the time because it was, ‘Do I sell this to get money to eat and live or do we play Tekken?’ He kept the PlayStation and sold other games he’d win at these sorts of events. It was an investment, as far as he was concerned, because the console allowed him to practise Tekken at home without having to spend loads of money working out combos at the arcade. That’s how good the PlayStation ports of Tekken were: fighting game pros – as pro as they were all those years ago – could train on PS1 and bring their homebrew strategies into the arcade and they’d just work.

“I don’t think we digested it as a conversion,” Hart remembers. “We were like, ‘Wow, we’ve got the arcade at home.’ It was so good that we didn’t even register that they’d ported this over. It was just, ‘Oh, the arcade’s in my house now, it’s just on a smaller screen with this tiny little control pad.’ “

Fans of Tekken in the arcade were being trained to fall in love with PlayStation games, whether they realised it or not. “The genius marketing from Sony there is that you got everyone into pad games, right?” Hart continues. “Because all the arcade guys were stick and buttons. But then you get home and it’s this little gadget, and you end up saying, ‘Oh well, I’m just going to play Crash Bandicoot on this,’ or, ‘I’m going to play Ridge Racer and all these other games now.’ So it converted you from arcade to console in a very sort of natural, organic way. I didn’t realise it at the time, but looking back, it’s like, oh yeah, that’s how we got there.”

As popular as Tekken was in arcades, PlayStation lifted the franchise up to new heights. Harada estimates Tekken on PS1 had “easily” 10 times as many players than the arcade version. Ridge Racer and Tekken became benchmark titles for the PlayStation as part of Namco’s “mutually beneficial relationship” with Sony. “So people were like, ‘If you’re going to buy a PlayStation, you need to buy these two titles so you know what it’s going to be like,’ ” Harada says. “Whereas if we made the choice to be on the Sega Saturn, for example, perhaps we couldn’t achieve the same level, we would’ve also had Virtua Fighter as a competitor on the same platform. So those unique circumstances really did launch the brand recognition for Tekken to another level.”

Ryan Hart makes an interesting point about why Tekken enjoyed so much success on PlayStation that I hadn’t considered before. Indeed, his point also makes sense in reverse, in that it helps to explain why Tekken was such a perfect fit as a PlayStation exclusive, even in those early days when we didn’t really know how a PlayStation exclusive was meant to look or feel.

It all has to do with Eddy, the Brazilian capoeira fighter who was introduced in 1998’s Tekken 3. The way Eddy was designed gets to the heart of Tekken’s PlayStation success: here we had a character who could be played well in the hands of a fighting game aficionado, yes, but, infamously, could do a hell of a lot of damage in the hands of a novice. Button-mash those two kick buttons on the bottom of the PS1 pad and Eddy would perform all sorts of hard-to-counter combos. Just keep button-mashing the kicks with Eddy and not only would you probably do okay, but you’d look good doing it.

Got a few friends round for a drink or two and want to play PlayStation? Pop Tekken on and give that one friend who doesn’t play games a controller and Eddy and they’ll be a fighting game maestro. Does your friend love Bruce Lee? Let them play as Marshall Law and mash the buttons. Do they love Jackie Chan? Give them Lei Wulong to play around with. It was Tekken’s cool accessibility that tapped into PlayStation’s true mainstream appeal: the post-pub gaming session, hazy weekends

Source link