In decades past, when undisputed heavyweight champions were the norm and not the exception, they inevitably created a great vacuum of power upon retiring. It was a mad scramble to fill the empty throne and present the world with its new pugilistic emperor and everyone wanted a piece of the action. Controlling the heavyweight champion meant controlling vast amounts of money and influence, and both are difficult to resist for those to be found in the darker corners of the boxing world.

In 1949 the International Boxing Club of New York was born, and one of the first orders of business was to figure out how to gain control over the heavyweight championship. By the mid-1950s the mafia, which was heavily involved in the IBC’s business, appeared to be closing in on the crown even with the federal government on its back.

The IBC operated out of New York, but its reach extended well into the Midwest, with Chicago being a key connector in the equation. It was there that Gene Tunney had defeated Jack Dempsey for the second time in the infamous “Long Count” fight back in 1927. More recently, Ezzard Charles had retained the heavyweight title in “The Windy City” with a 15 round decision over Joey Maxim in 1951. Chicago had hosted considerable action in the last decade or so, and it was ready for more.

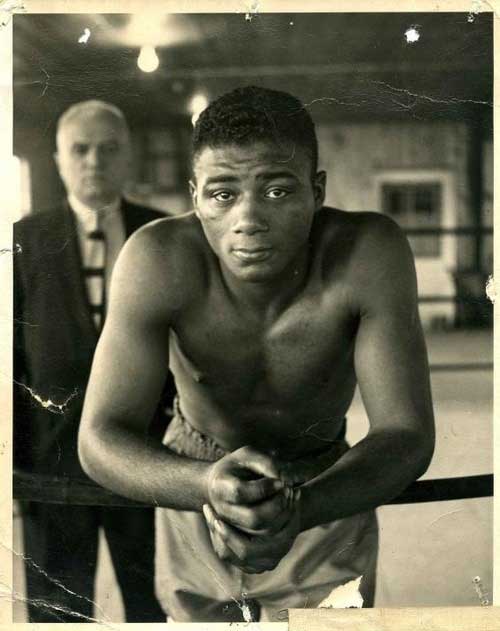

Rocky Marciano, a popular champion who hung out with mafioso and was rumored to have mob ties, retired in April of 1956 to spend more time with his family and nurse a few nagging injuries. His final opponent, Archie Moore, thumbed his nose at Father Time and took aim at the vacant title despite his advancing age of, depending on who you believed, 39 or 42. Archie himself wasn’t sure which number was right and would later say, “I have given it a lot of thought and have decided that I must have been three when I was born.” He had over 180 fights under his belt though, and standing in his way was a 21-year-old fighting out of New York named Floyd Patterson, a former Olympic gold medalist with fast hands and a dangerous left hook.

Patterson vs Moore was set for Chicago Stadium and while “The Old Mongoose” was widely considered dusty, he was still favored to become the next champion. Archie’s huge advantage in experience made him a 6-to-5 favorite, though a fractured right paw suffered by Patterson in a ho-hum title eliminator the previous June against Tommy “Hurricane” Jackson was likely a factor as well.

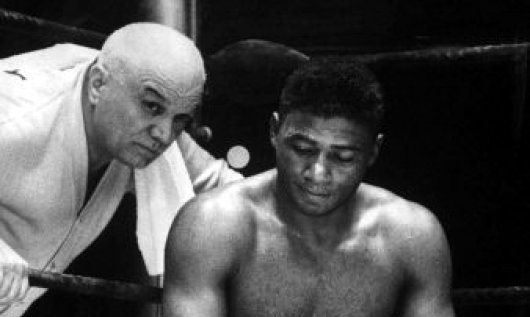

Strangely, Patterson’s camp was set up at a local horse racing track called Sportsman’s Park, where he did his roadwork on the raceway and sparred in a luxurious section of the grandstand in a makeshift ring. Cus D’Amato, Patterson’s trainer and manager, had come to be a thorn in the side of the IBC and out of fear that someone might try to poison his fighter, D’Amato slept so that his cot blocked the doorway to Patterson’s room.

As it turned out D’Amato had reason to be suspicious; it was later revealed Moore had cut a backroom deal with the IBC, offering them exclusive rights on promoting the heavyweight title in exchange for a higher guarantee should he win. The deal went against the Illinois Athletic Commission’s regulations, which mandated that both men receive a thirty percent cut of the fight’s total revenue. But D’Amato had Patterson study to defeat his opponent, which would take the IBC out of the equation entirely.

Dan Florio, who had also trained Tony Canzoneri and former heavyweight champions Jersey Joe Walcott and Gene Tunney, assisted Cus and he made it a point to have Floyd repeatedly view tape of Rocky Marciano’s defeat of Moore. He later noted that Patterson became agitated every time he saw Archie deck Marciano with a right hand in the second round. But the intention was to have Floyd see for himself what he had to be wary of against Moore, namely that right hand lead. When Marciano had led with his right, Moore countered with his own, so rather than pecking at Moore and allowing him to work how he wanted, Florio and D’Amato devised a strategy to keep the pace steady and rob “The Old Mongoose” of an opportunity to get going offensively.

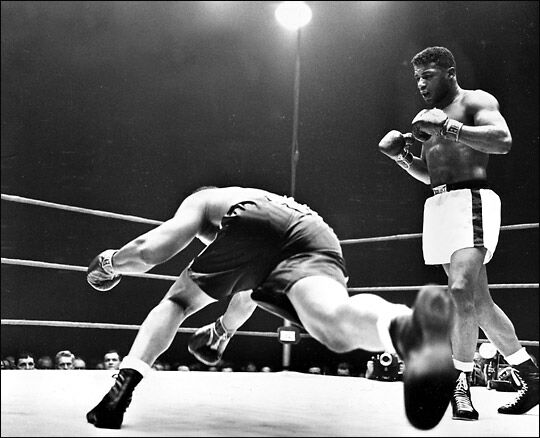

When fight night came, Moore was up to his old tricks; he would lean and sway to one side, away from his opponent in order to goad them into committing to a punch he could avoid before countering. He did it well in round one at times, but Patterson fought with his gloves high, much of his offense and defense predicated on bending his waist and weaving past Moore’s punches. The strategy confused Moore and he had few opportunities to work his counters, and by the end of round two Patterson had gained control of the fight.

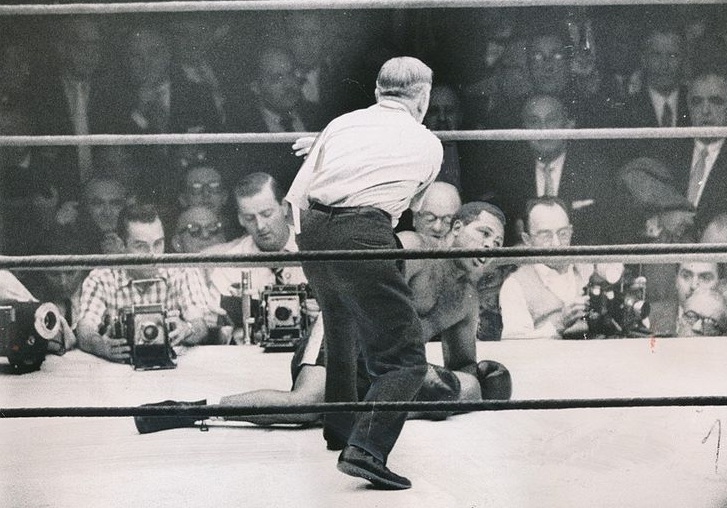

In round three Patterson opened a gash on Moore’s left eyebrow, and in the fourth Archie was sent to his corner looking more rickety than ever. A left hook in round five sent “The Old Mongoose” down and seemed to steal his legs out from under him. After he rose, a single right hand brought Moore to a knee and put him there for the count.

After the bout, Patterson learned he was a new father from a reporter who handed him a wire photo of his wife Sandra holding his new little girl back in New York. Seneca Patterson had in fact been born a few hours prior to the fight, but Floyd’s team kept the news from him so as not to distract him from the task at hand. Skipping out on his victory party, Patterson and hightailed it back to New York to go meet his daughter.

For his part Moore admitted defeat. He would later say that an ex-lover attempted to falsely accuse him of criminal sexual activity and blackmail him prior to the fight, accounting for his poor performance. He would later state: “I’ve lost many fights but never did I lose one in such a sorry fashion as the night I fought Floyd Patterson.”

After the the biggest win of his career, Patterson said, “I knew that tonight I was opposed by one of the smartest boxers and sharpest punchers in the business, but I never had any doubt about what I could do to him.” He became an instant celebrity, appearing in commercials and on game shows, including “What’s My Line?” He also became the youngest ever heavyweight champion, beating the record of Joe Louis, who was 23 when he himself won the biggest title in sports. — Patrick Connor