rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

Back in January, I wrote an article called “Unfuzzing the Strike Zone.” The premise was pretty simple. As umpires have grown more accurate, as the edges of the strike zone have gotten clearer and more distinct, the strike zone has effectively gotten smaller. Misses go both ways, but there’s a big difference between an incorrectly called ball and an incorrectly called strike. Calling a pitch inside the zone a ball doesn’t shrink the effective size of the zone, but calling a pitch outside the zone a strike does make it bigger. As long as a pitcher knows it’s possible to get a strike call out there, they’ll consider it part of the zone. Little did I know that as I was writing that article, Major League Baseball was preparing to test its exact premise.

The strike zone has steadily shed its fuzz over the past 23 seasons, but on Thursday, Jayson Stark and Ken Rosenthal reported in The Athletic that the league has decided to break out a sweater shaver. Over the offseason, the Major League Umpires Association came to a new agreement with MLB. Part of the agreement included tightening the standards by which ball-strike calls are graded.

Umpires used to have a two-inch buffer around the edge of the strike zone, meaning that if they’d missed a call by fewer than two inches in either direction, the call would still go down as correct in their assessments. Having that buffer is necessary because calling balls and strikes is extraordinarily difficult. It’s extremely rare for an umpire to get every call right even in a single game. The new border is just three-quarters of an inch on either side, a reduction of 62.5%. The league is demanding a less fuzzy strike zone.

How have players felt about the zone after one month? Angels catcher Travis d’Arnaud gave a quote that was pretty representative of the sentiments expressed throughout the article: “Everybody’s zone has shrunk. Every (umpire) across the league.” Stark and Rosenthal also backed up those assertions with numbers, and we’re going to dive very deep into the numbers tomorrow. For now, I’ll just tell you that accuracy has indeed ticked up some from last season.

The article also expressed a major conflict. The league maintains that teams were briefed about the new rules, but none of the at least 28 players, coaches, executives, and analysts interviewed remembered hearing about this information. We’re not going to wade into that particular morass; Michael Baumann summed up the situation nicely on Bluesky on Friday. “I remain puzzled by MLB’s propensity to turn innocuous developments into controversy purely through poor communication,” he wrote. “They’ve tightened standards on umpires in order to get closer to the rulebook strike zone — how can that possibly be anything but a good thing? And yet!”

For two other reasons, I was planning on checking in on the strike zone even before The Athletic’s article came out. On April 26, Susan Slusser of the San Francisco Chronicle reported that the Giants, who boast the game’s preeminent pitch framer in Patrick Bailey, are complaining that the top of the strike zone in particular seems to be shrinking. “I think at the top of the zone, there’s been a lot missed,” Bailey said. “That’s kind of the area that every catcher is struggling, relatively speaking.” The final piece is something I’ve been meaning to check in on since last May. At the time, I noted that ball-strike calls were less accurate, but that they would likely improve. I made that assertion because the data showed that umpires tend to get more accurate as the season goes on. So those are the three questions we’ll address:

Did umpires actually get better last season?

What can we learn about the effects of the new umpiring standards?

Are they related to the complaints of the Giants?

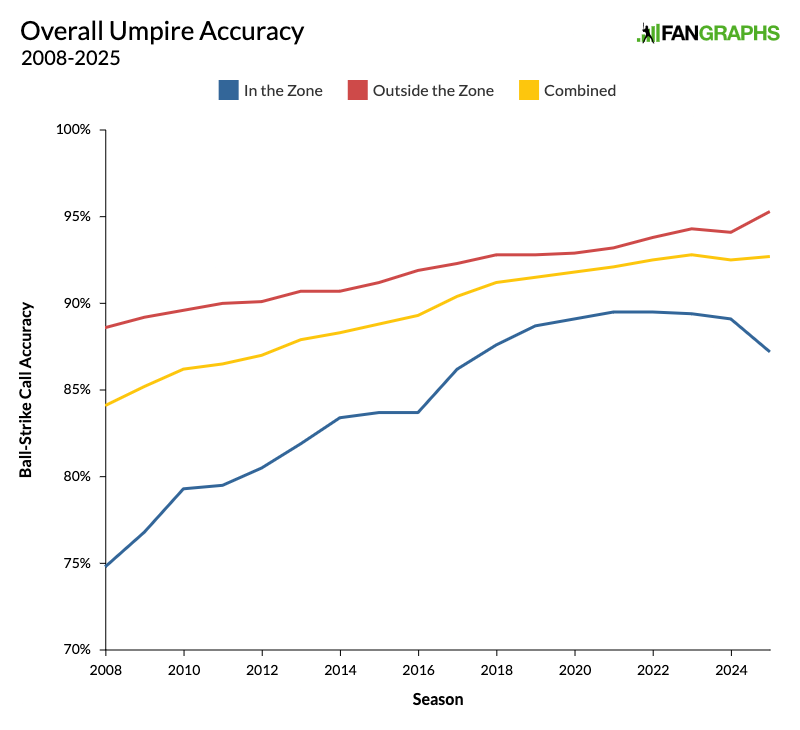

Today we’re going to tackle the first bullet point. Let’s start with the big picture. Here’s the accuracy of all ball-strike calls during the pitch tracking era, which started in 2008.

The yellow line shows the overall rate, and you’ll notice right off the bat that in 2024, for the first time ever, it didn’t go up. It went down. Umpires did get better as the season went on, but overall, they were worse than they’d been during the previous season. Umpires made the correct call 92.8% of the time in 2023, but that fell to 92.5% in 2024. This is a big deal! It had never happened before. Since the moment we started measuring umpires, they’d done nothing but get better and better. For the first time ever, in 2024, they got ever so slightly worse. Before we dig into that, I want to show you the numbers from the shadow zone, Statcast’s term for the area that’s one baseball’s width from the edge of the strike zone on either side.

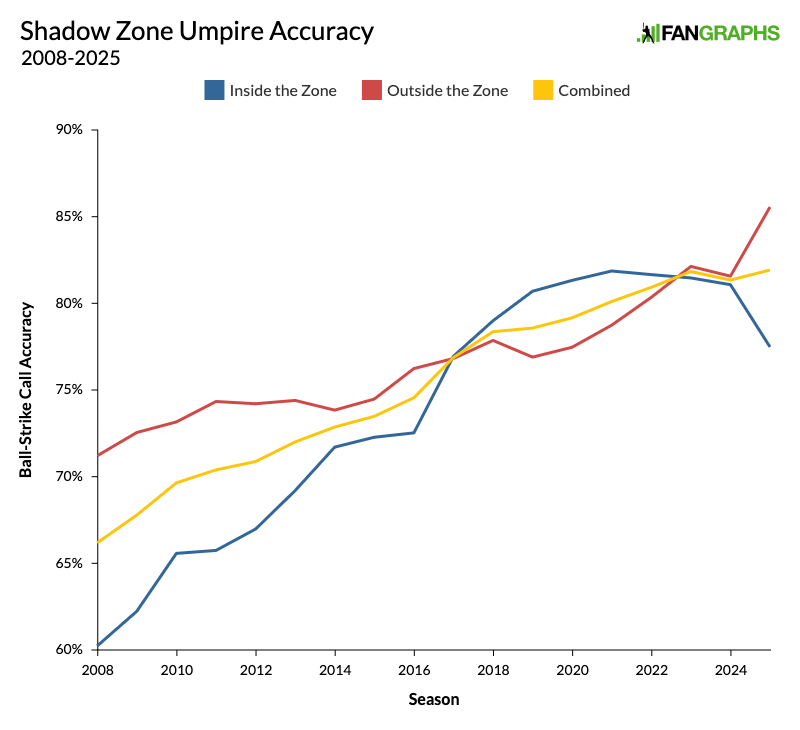

We should care less about the overall stats than about the shadow zone for a very simple reason. The composition of the pitches that umpires have to call can change slightly from year to year. So far this season, 39.49% of takes have been in the shadow zone, the highest proportion we’ve ever seen. With so many takes right on the edge, the calls have been more difficult this season. These days, umpires are so good that they almost never miss calls outside the shadow zone, so it makes sense to focus on the group of pitches that actually matters and throw out everything else that could skew the numbers.

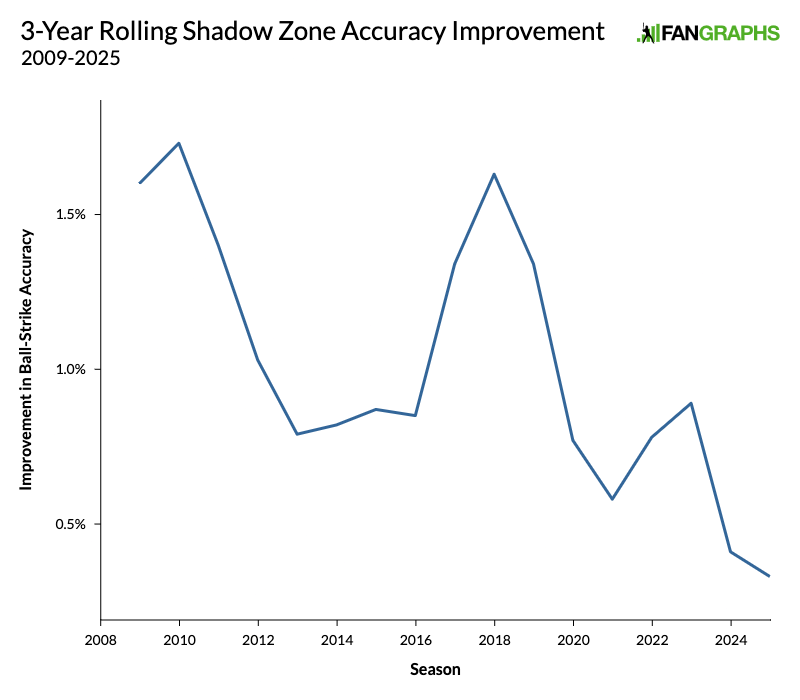

This graph makes me think the league picked the right moment to tighten the standards for umpires. The effect is much smaller, but once again, the yellow line ticked slightly down in 2024 for the first time ever. Accuracy dropped from 81.8% in 2023 to 81.3% in 2024. It’s a rounding error, but that doesn’t mean it’s insignificant. I care much less about the number going down slightly than about progress seeming to stall out. The graph below gives a slightly different view of the same information. It shows the amount of year-over-year improvement in shadow zone accuracy, but it combines three years at a time to smooth the graph out some and give you a sense of the overall trend.

The graph has some peaks and valleys, but the trend is clear. Umpires have been getting better and better, and there’s less meat on the bone than there once was. To mix our food metaphors, the better you get, the harder it is to keep improving because the low-hanging fruit is gone. That line is now coming perilously close to zero. Over the years, the composition of the umpiring corps has changed. These days, the league is full of young umpires whose promotions through the ranks depended on receiving good marks from Statcast. They’re much more accurate – that is to say better at adhering to the Statcast zone – than the older umpires they replaced. In that sense, improvement has been organic. New umpires who spent their whole careers trying to meet the demands of the Statcast zone replaced older umpires who didn’t, and the accuracy rate naturally went up. But that could only last for so long. It’s only a one-year sample, but it seems possible that in 2023, umpires got as good as they were going to get under the current system. They’d finally stopped improving, so it seemed like an apt time to give them a push.

A while back, I read The Perfectionists by Simon Winchester. It documents the history of precision engineering from the 18th Century to today. The overriding lesson was about the power of measuring. It’s hard to get better at anything unless you know for certain what you’re looking at, and that’s hard to know unless you can measure it with precision. This truism applies to pretty much any endeavor. For example, I wrote about the transit method for planetary discovery, last week. By developing a telescope sensitive enough to measure the tiniest changes in the brightness of stars, scientists discovered hundreds of thousands of planets. Whole new worlds, discovered simply because we could finally measure light with enough precision. Every day from February to November, umpires are asked to do a near-impossible task, and ever since the league started grading their efforts, they’d gotten better at it. But after decades of continuous improvement, we got our first hint that they might be approaching their limits. As a result, they’re now being measured with greater precision. The 2025 season has become an experiment to see whether that change will force them to improve their own precision and to make more accurate calls. We’ll look at the early returns tomorrow.