In 1982, after being treated for a detached retina, Sugar Ray Leonard retired from boxing. Two years later he attempted a comeback, which was quickly aborted after an underwhelming performance against contender Kevin Howard. Time passed and all assumed Ray had walked away for good. His decision to return a full three years later to challenge Marvelous Marvin Hagler was universally viewed as a terrible idea, but Leonard shocked the boxing world with a close decision win over Hagler to take his third world title. Again, time passed and many assumed Leonard, having defeated his most formidable foe, was content to let that great triumph be his last. Then, out of nowhere, a match with little-known light-heavyweight titlist Donny Lalonde was announced.

Looking back, the defining characteristic in Sugar Ray Leonard’s career following his loss to Roberto Duran in 1980 was its self-serving selectivity. Strongly influenced by lawyer Mike Trainer, who effectively worked as his manager and who believed boxers should focus more on the bottom line, Leonard decided that what happened in his first meeting with Duran must never happen again.

In other words, ever after Ray would never allow circumstances or the desires of others to dictate his actions. That first clash with Duran had been less a conscious career choice on Leonard’s part as much as a bending to the desires of various vested interests and the public. Duran vs Leonard was the biggest and richest match to be made at the time — Leonard’s eight million dollar purse was a record — but in the ring the nature of the situation worked in Duran’s favour, not Sugar Ray’s. Intimidated by the ferocious Panamanian and wanting to satisfy public demands, Leonard’s desire to prove himself adversely affected his tactics in the fight. He chose to hold his ground against Duran in Montreal, battling mano-a-mano, and while in the process he gave the sport and the fans a thrilling war, the end result was his first professional defeat.

Presaging the career choices later on display from one Floyd Mayweather Jr., Leonard ever after would conduct his career on his terms and in his favour, and his alone. He signed few exclusive deals with networks or promoters and he made the final decisions on who and when he fought. He pushed for an immediate rematch with Duran primarily because he knew the Panamanian would be hard pressed to get back into peak condition by fight time. After his thrilling, come-from-behind victory against Thomas Hearns in 1981, many called for a rematch but Leonard, against all expectations, dismissed the idea of facing either “The Hitman” or Duran again. Over the next several years he appeared to enjoy surprising the public, making unexpected announcements such as his retirement in 1982, his immediate re-retirement after his comeback win in ’84, and his decision to challenge Hagler.

It is an acknowledged fact that Leonard waited to face Hagler until Marvelous Marvin showed definite signs of decline, Marvin’s surprisingly two-sided and difficult win over John Mugabi prompting Ray to finally throw down the gauntlet. Similarly, his decision to at long last give Hearns a rematch in 1989 had much to do with the fact that Tommy hadn’t looked good in years. Opportunism had become the name of the game for Leonard and many boxing fans resented him for it, primarily because of all the great fights that didn’t happen as a result, but also because of what it revealed about his character. In the last few years of his career, Sugar Ray went from being one of the most popular figures in the sport to being, among serious ring fans, one of its most reviled.

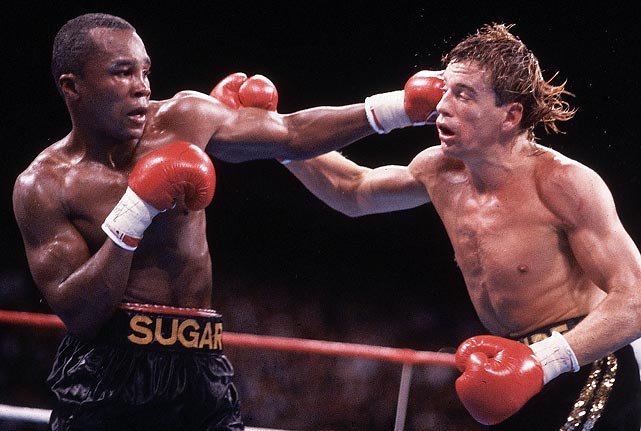

And Leonard’s decision to face Donny Lalonde is perhaps the quintessential example of his refusal to listen to the desires of others and to seek the greatest personal gain under the most favourable circumstances. No one had asked for this fight. And outside of hardcore fans, few knew anything about Lalonde. But for Leonard, the prime attraction of the match-up was that the opponent wasn’t named Hearns, Hagler or Duran. The bout didn’t fit into anyone’s expectations. It represented Leonard asserting his independence, while at the same time adding in a measurable way to his accomplishments; both Lalonde’s light-heavyweight belt and the newly minted WBC super-middleweight title were to be at stake.

For boxing fans, the match was an attraction for one reason: intrigue. This was only Leonard’s fourth contest in five years and his first since April of 1987. What did he have left? Would this be his final fight? Who exactly was Donny Lalonde? And what was Ray doing taking on a light heavyweight? Though in truth, Leonard had the latter angle covered as well; to get the fight and the big payday, Lalonde had to agree to a catch-weight of 168 pounds, seven pounds below the light-heavyweight limit. Further, as a guarantee he would comply, the champion pledged to forfeit one million dollars for each pound beyond the agreed upon limit if he came in overweight. The result was Lalonde’s camp fretted about the scale instead of focusing on the battle at hand. A drained Lalonde weighed in the day of the fight at 167 with his clothes on, while Sugar Ray weighed 165 with rolls of silver dollars in his pockets.

Before the bout Leonard hinted broadly that this could well be his last ring appearance. Despite this, Caesars Palace in Las Vegas did not sell out and pay-per-view sales were respectable but not outstanding. It appeared there was a price to pay for evading the public’s expectations. But others paid a price too: this was Ray’s first fight without Angelo Dundee in his corner. Again, refusing to fulfill the expectations of others, Leonard had chosen not to pay Dundee the customary percentage following the huge win over Hagler. Dundee then demanded a written contract before agreeing to help Leonard prepare for Lalonde, but the man who had skillfully guided Ray to the title and boxing stardom was rebuffed.

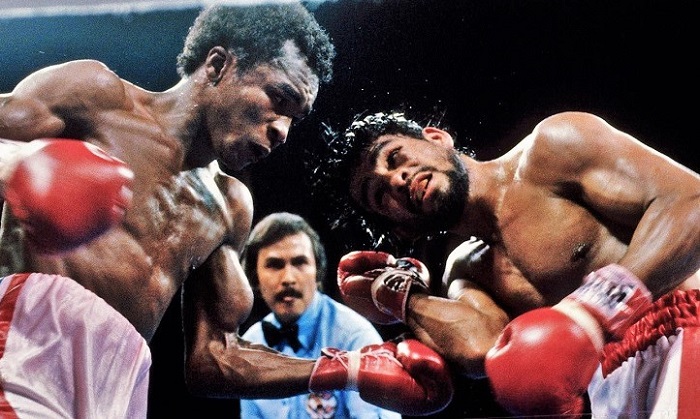

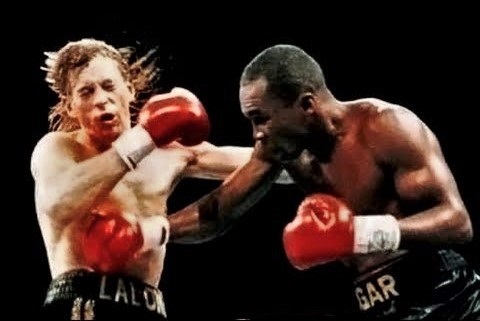

Leonard vs Lalonde was a somewhat odd affair, though certainly not lacking in action. The champion, an awkward, ungainly boxer, used his height and reach advantages to good effect in the early going as he set a brisk pace behind a long left jab. Lalonde’s stated theory was that Hagler had failed to pressure Leonard enough, had allowed him to take time off, and that in contrast he intended to make the older man work. And over the first three rounds he did just that. Meanwhile Leonard appeared rusty and not terribly interested. It was the underdog champion fearlessly taking the fight to his opponent while a subdued crowd wondered when Ray would get going.

But in the fourth it was Lalonde, not Leonard, who woke up the crowd as he caught Ray with a thumping right cross on the forehead that toppled the former champ. A stunned Leonard rose and then hung on as the champion tried to take advantage, attacking with more wild rights, most of them missing the target. The rest of the round was a brawl that saw both fighters land telling shots and left Ray with a cut on the bridge of his nose.

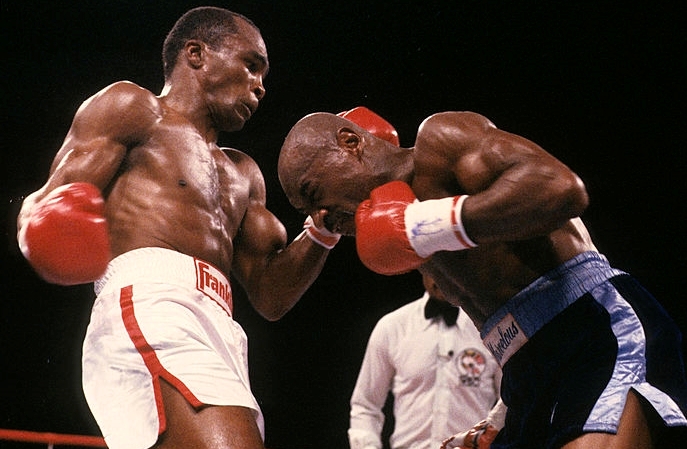

But now Leonard was awake too. And he became a different fighter, using upper body movement and a sharp jab with the right hand behind it to turn the tables. Near the end of the fifth he connected with his first authoritative blows, whistling left hooks and powerful rights, and had Lalonde in trouble before the bell. The sixth was a slugfest with both men hurt and the seventh was more of the same, but Ray’s greater accuracy and Lalonde’s mounting fatigue were now defining factors. In the eighth Leonard landed left hooks at will but Lalonde, to his credit, never stopped slinging back heavy right hands.

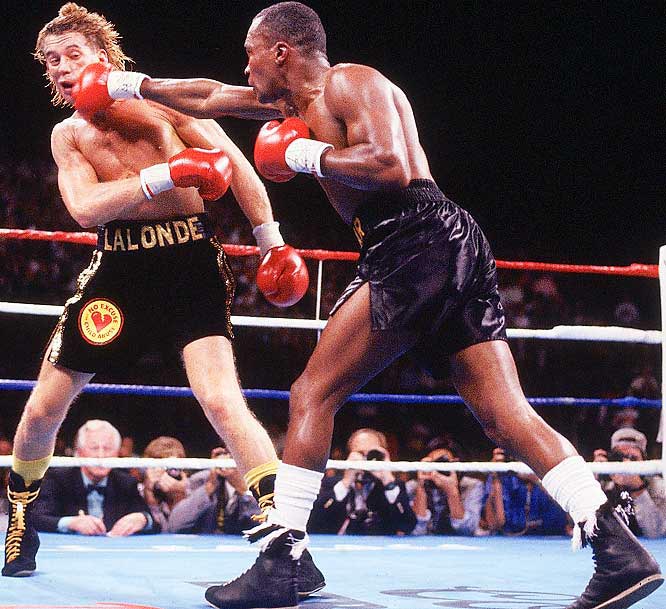

As round nine began Leonard appeared in control, but midway through the champion surprised him with a two-fisted volley of power shots that had Ray briefly in trouble. Lalonde kept throwing but then Leonard gathered himself and counter-attacked with fury. A thudding jab set up a vicious right which buckled Lalonde’s legs and now it was Ray’s turn to launch a barrage of heavy artillery. Backed to the ropes, Lalonde ate punch after punch before a vicious left hook put him down. The champion struggled to his feet with difficulty and ruefully gestured at Leonard as if to acknowledge his opponent’s superiority. It almost appeared as if he thought the fight was over. His eyes widened as the referee waved Leonard back in and Ray pounced with two powerful rights and a finishing left. Lalonde pitched to the canvas again and the fight was stopped.

Leonard had his win, two more world titles, and another big payday but none of it came easy. No one could remember the last time Ray had been cut and knocked down in the same fight, or had taken so many solid punches. Loud calls for Sugar Ray to retire for good were heard now, but Leonard, as ever, would do things his way, never following the expectations of others, a characteristic which guaranteed his career could not end on a winning note. – Michael Carbert