rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

Dangling precariously above a curious crowd of thousands that had gathered around Mills Field at San Francisco’s municipal airport, Fred Mahan panicked. The world title challenger’s parachute had become ensnared in the plane’s stabilizer during a publicized skydiving attempt. The plucky contender seemed doomed to a horrific death.

Twenty three years earlier, Federico Mesa was born in Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico. At eight months old, he fell from his highchair and permanently lost his hearing. As a result, he never developed the ability to speak.

As a teenager, Federico and his father, Jesus, worked as laborers, making several trips across the border to work in Del Rio, Texas. Eventually, the family settled in the nearby small ranch town of Brackettville. After the death of his father, Federico’s mother, Josephine, soon remarried. She wed a man named William Mahan, a Massachusetts-born son of Irish immigrants.

In Texas, Federico Americanized his name to Fred. He began to box professionally as a bantamweight in 1923 at the age of seventeen and adopted his stepfather’s surname. Immediately upon turning pro, the press slapped him with an insensitive nickname: “Dummy.” As early as 1937, the National Association of the Deaf condemned the use of terms such as “dumb” and “mute,” but during his career, the press habitually used these terms to describe Fred Mahan.

Mahan spent the first five years of his career traversing his adopted home state, learning from plenty of losses and savoring the odd victory. In February of 1928, he went west to California in search of bigger fights. The California State Athletic Commission refused to issue Mahan a license in light of his “physical deformity.” His short-lived disappointment evaporated when Fred “Windy” Winsor caught wind of Maher. Winsor, who had managed a young Jack Dempsey and possessed an unparalleled gift of gab, promised Maher fights if he joined Winsor’s stable. Mahan packed his belongings — which consisted of a toothbrush, a comb, and an extra tie — into a cigar box and traveled eastward with his new manager.

After fights in Denver and Chicago, the pair set up camp in Columbus, Ohio. There, Mahan beat two solid fighters, Meyer Grace and Cuddy DeMarco, along with a host of journeymen. His only loss in the state came in a return bout against Grace, who was also known as Young Jack Dempsey.

A proficient lip reader, Mahan was a well-read and intelligent man. He devoured any newspaper he could find and loved books. In Columbus, he became an instructor at the Ohio School for the Deaf.

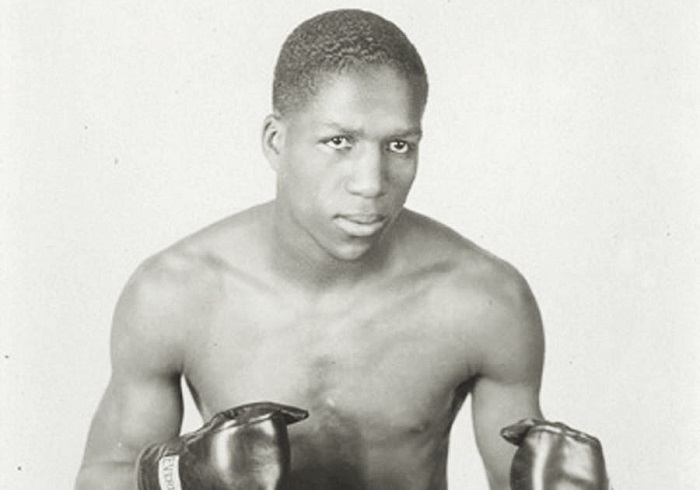

Under Winsor’s tutelage, Mahan developed both in and out of the ring. He transformed into a puncher. With broad shoulders and bulging powerful arms, he could crack with either hand. After the successful Ohio stint, Winsor decided to take Mahan back to California at the beginning of 1929.

The California commission reversed course on Mahan after he passed a test showing he could follow the rules of the ring. He was even complimented for his “uncanny brightness.” In over 75 fights to that point, Mahan had never been reprimanded for hitting late because he could feel the vibrations of the bell. In California at the time, coaches were not allowed to yell instructions during the rounds, so Winsor learned sign language to circumvent the rule. Mahan managed to keep one eye on Winsor’s instructions and one on his opponent’s movements.

After scoring six knockdowns en route to a second round stoppage of Johnny Priston, Mahan faced future welterweight world champion, Young Corbett III, an all-time great southpaw most contenders preferred to avoid. Two weeks after recovering from jaundice, Mahan lost by decision in a competitive fight that raised his stock and earned him a shot at junior welterweight world champion Mushy Callahan for the title.

Mahan’s May 28 challenge against Callahan at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles was a wild affair. A short right put the champion on the seat of his trunks in the opening round. Callahan scored a knockdown of his own to open the second. Mahan then floored Callahan for a second time before Mushy evened the score in a second stanza that saw three total knockdowns. In the third, the champ connected with a right uppercut, putting Mahan down face first and forcing Winsor to throw in the towel.

Mahan came back with three knockouts in under a month that summer, which led to a big fight back at the Olympic against future middleweight world champion William “Gorilla” Jones, another contender no one was too anxious to fight. By this point, the Mexican-American warrior had become so popular that he traded in his cigar box for a massive trunk in which he kept suits for every day of the week, replete with matching ties. On August 20, Jones punished Mahan’s midsection until he took a knee in the sixth round. The count wasn’t clear, so an attentive Mahan accidentally rose just after the referee reached ten, resulting in an unfortunate knockout loss.

Despite the defeat to Jones, Mahan received a major opportunity against welterweight world champion Jackie Fields in an over-the-weight bout. Mahan brought the fight to Fields in the first, but the champ’s body shots set up a left uppercut that knocked out Mahan in the second round. Mahan quickly rebounded with five wins in a row, four by knockout, before his fateful flight.

For months Mahan had been excited about his skydiving adventure set for February 23, 1930. He hoped the experience would restore his hearing. He had reportedly skydived before and claimed the change in air pressure caused him to briefly regain his hearing after landing. A large crowd of several thousand gathered to watch the jump in what some in the press dismissed as a publicity stunt. But the danger was real. Fred Winsor begged Mahan to reconsider.

Colonel Henry Abbott, an experienced pilot who had flown airplanes during World War I, operated the plane out of which Mahan would be jumping. Abbott had invented the parachute strapped to Mahan’s back. He communicated to the boxer that upon his descent he should count to six before pulling the ripcord.

Instead, Mahan became overly excited and pulled the ripcord too quickly. His life flashed before his eyes during the terrifying 25 seconds it took for him to succumb to gravity’s will. The crowd watched in horror as Mahan reached a chilling terminal velocity of 173 feet per second.

Immediately after the accident, a distraught Winsor sobbed, “He would’ve been welterweight champion.”

The fighter who had willed himself into a popular and inspirational hero was gone. At Mahan’s funeral, Winsor bumped into his estranged wife Genevieve, who was also close with the deceased boxer. Then and there, the couple decided to reconcile. Even in death, Fred Mahan touched the lives of those near and far. –David Harazduk