There really was nothing left to prove. Why Mickey Walker felt an assault on the heavyweight division was necessary, nobody still living knows. It likely had much to do with money and the way he and his manager, Jack “Doc” Kearns, burned through it with all the liquor and high living. History and legacy had to have been lesser concerns; Walker had already been welterweight and middleweight champion and had even kept matters close with one of the best ever in Harry Greb. Then again, Walker didn’t just take a stab at some paydays with his foray into big man territory. Instead, it was a full-fledged campaign on a division that lacked a dominant champion.

Mickey spotted heavyweight spoiler Johnny Risko 30 pounds before decking and defeating him in November of 1930, and Kearns urged Walker to call out Young Stribling, as well as former heavyweight champ Jack Sharkey, who was a few months removed from losing the title by disqualification to Max Schmeling. But Sharkey had his heart set on his old title and stayed out for over a year waiting on his rematch.

Two years of failing to defend his middleweight crown had gone by with a suspension from the New York State Athletic Commission to boot, so Walker relinquished the title rather than attempt to make the weight once more. As reports of a likely Walker vs Sharkey match-up flooded papers in mid-June, Colorado senator “Wild” Bill Lyons, who had previously served as Jack Dempsey’s timekeeper, caught wind of Walker’s abdication of the title. “I knew he couldn’t make the middleweight limit anymore,” Lyons said. “And here is something else you can mark down in the book: Walker’s first fight as a heavyweight will be against Jack Sharkey, and boys, what a scrap that will be.”

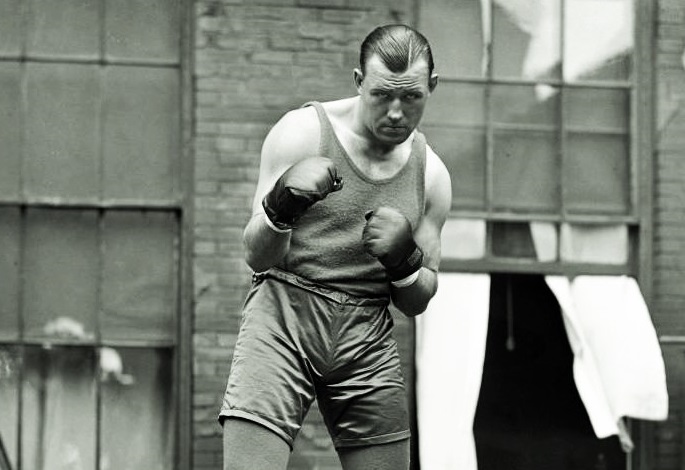

Walker was as venomous as they came and had battled through a few larger opponents already, so he had little to lose when he began training in Orangeburg, New York, a camp that would later be shared by lightweight great Tony Canzoneri and wrestling champion Jim “The Golden Greek” Londos. Much of the previews centered on how “The Toy Bulldog” was likable but also old, scarred and weathered, and the 30-year-old started out a 2-to-1 underdog when the bout was finalized for Ebbets Field, which was Brooklyn Dodgers territory. Successful promoter James Johnston, a former street tough and pro fighter, stepped in to handle affairs.

Sharkey’s trip to the Schuyler House in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey for training was reportedly delayed by bad weather. But it was just as likely that Sharkey waited to leave for Boston to second a fighter he was co-managing, Ernie Schaaf, who was fighting Jim Maloney again on July 10.

In fact, much of Sharkey’s focus was on rematching Schmeling and Stribling, and heavily trash-talking both every chance he got. Perhaps it was the size difference that left Sharkey dismissive of Walker’s challenge, but a week before the bout he told INS reporter Les Conklin, “While I’m not taking Mickey lightly, I’d be a so-and-so if I said I couldn’t lick a middleweight. Walker’s only chance is to get in close, but he’ll never do it. I’ll hold him off with my left and make a nice whittling job of it, slow but sure.”

Walker was susceptible to boxers; he was rarely overpowered or strong-armed, but he had issues with movers and fighters with quick hands. Sharkey didn’t fall into either of those categories, but odds widened to 3-to-1 for “The Boston Gob” shortly after he was seen felling sparring partners in a particularly rigorous final workout.

But just a few rounds into the match saw Walker ignoring the odds and reddening Sharkey’s right cheek and his ribs on the right side. Said W.A. Hamilton, “Sharkey had the time of his life trying to locate Mickey with a solid wallop, and missed more right-hand punches than he was ever known to in any previous fight.” The career-high 169 pounds was wearing on Mick though, and he was caught up to, rocked and cut above the right eye in round five.

Visibly much larger, Sharkey clinched Walker, leaning on him in close, rabbit punching, butting and hitting low, before connecting with hard jabs from the outside. Walker was landing from a crouch when he could, but Sharkey was still markedly bigger and stronger, and it showed in the middle rounds. But in round nine Walker hurt Sharkey with right hands upstairs mixed with hooks to the liver, and he battered him in the tenth before Sharkey got his bearings and went back to stalling for a few rounds. Again in rounds 13 and 14 Walker found the tired, stationary man from Boston easy to find, and Sharkey held and hit to get out of trouble. And it worked, as in the final, bruising round Sharkey tore a wider cut on Walker’s eye and almost floored him before the bell.

In context, it was an inspiring performance from the comparatively diminutive Walker, while a resoundingly disappointing one from the heavyweight ex-champion. Damon Runyon said from ringside after the draw was announced, “It proves Walker’s caliber as a fighting man.”

Former champions James J. Corbett wrote, “Sharkey gained plenty of cash tonight but lost tremendously in prestige.” All told, Sharkey was paid just over $60,000 for the no-win affair. Walker got over $40,000, while the Milk Fund, a charity organization that provided needy children with milk, got half, or about $100,000.

The same temper that lost Sharkey the heavyweight title on a low blow was probably to blame for suffering a draw to a much smaller man, as referee Arthur Donovan warned Sharkey for foul punches and butting several times, and he cast his ballot for Walker. Further, when Walker vs Sharkey was signed, Jack pounded the table with a wild look in his eyes, ranting about Schmeling and warning against the new champion taking any other fights but a rematch. It was hubris and rage and it showed he was looking right past Walker, a fact which showed again in the fight.

Sharkey eventually got that rematch and won the heavyweight title from Schmeling by controversial split decision. But not long after he lost to Primo Carnera and his days as a championship threat were over. Meanwhile Walker moved on to beat some more heavyweights before falling to Schmeling and Risko and then Maxie Rosenbloom for the light heavyweight crown, and it was mostly downhill after that. Alas, these accomplishments weren’t needed; Walker’s place among the heap of greats was, and remains, very secure. — Patrick Connor