He was just thirty-two when he left this world but if, as the old saw goes, only the good die young, then Tiger Flowers could never have escaped his fate. If ever there was a man of virtue and integrity to be found within the squared circle, it was Theodore Flowers, the son of religious, God-fearing parents, a man who had to turn his cheek many times outside of the ring, such being the plight of any black man in America at that time. But no one could ever mistake Flowers’ kindness and godly ways for weakness; this was a born warrior who fell in love the moment he first laced up a pair of hitting gloves, a boxer who competed an astonishing 141 times in less than a decade.

Flowers was from Atlanta, but it was the legendary fight city of Philadelphia that introduced to fisticuffs the man who would go on to become one of boxing’s greatest ever southpaws. Young Theodore had travelled to “The City Of Brotherly Love” during World War I to work in the shipyards and more or less by chance, he wandered into a gym which happened to be owned by no less a boxing luminary than Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, who, as it happened, was not prejudiced and allowed men of any colour or creed to train there. The former light heavyweight champion of the world was impressed with the younger man’s natural talent and encouraged him to keep training.

Theodore fell in love with the sport and when he returned to Atlanta he set about pursuing a professional career, despite the objections of his church and his mother. “I’m a professional pugilist because I believe God meant me to be what I am,” stated Flowers. “The Bible tells me that it is not wrong for a man to fight for his livelihood.” He turned pro in 1918 though his career really didn’t get moving until 1921. He fought 13 times that year and by the end of it he

was a force to be reckoned with, more than holding his own against serious talents such as Panama Joe Gans and Kid Norfolk.

His nickname of “The Georgia Deacon” was entirely appropriate. He carried his own little bible with him at all times, though he never prayed for victory in the ring. “I might meet a better and stronger man and lose the fight. Then I might be tempted to doubt the Lord, so I always wait until the fight is over and then I give thanks for the strength that has brought me safely through.”

Whatever the outcome, Flowers accepted the decision of the officials without a word of complaint or protest. But in this regard, his faith was tested many times as he was the victim of more than a few prejudiced verdicts during his career. Alas, this was just routine business for a black fighter at that time. But no matter the end result, Flowers always shook his opponent’s hand and offered courtesy and respect.

During the fight was another matter entirely though, as his other nickname, “Tiger,” was equally appropriate. A converted southpaw, he battled furiously, throwing a storm of leather at his adversary while proving hard to hit in return. He had an unconventional style all his own. Crafty, slippery and amazingly busy, his sense of timing and distance, along with his speed, awkwardness and great physical strength, made him a world champion and an all-time great middleweight. His only notable weakness was a less than iron-clad chin.

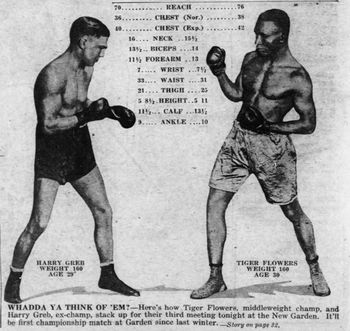

Like all black pugilists of that time, Tiger Flowers found it difficult to obtain matches with white fighters and often had to fight his fellow “colored” boxers many times over in order to make a living. In the end, premature as it was, he compiled a record of 132 wins, 17 losses, 8 draws, and 4 no-contests over the course of little more than nine years, an astonishing rate of activity. Flowers’ most famous fights are his battles with Harry Greb and Mickey Walker, but he also boasts wins over top-notch talents such as Lou Bogash, Johnny Wilson, Frank Moody and Jock Malone, not to mention numerous battles with light heavyweights and even the big men. Like all of the greats of that time, Tiger was more than willing to mix it up with men much larger and heavier.

In 1924 Flowers met fellow all-time great and current middleweight champion Harry Greb. To the surprise of many, Flowers got the better of it after ten rounds, though the only way he could have received an official win was if he had knocked “The Smoke City Wildcat” senseless. Instead the title stayed with Greb though many thought he was fortunate not to have lost it. Greb himself told writer B.W. Dickerson, “Flowers is the greatest boxer I ever faced in the ring. He can beat heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey … He gave me a fight I will never forget and it showed me a lot of things about boxing that I never knew before.”

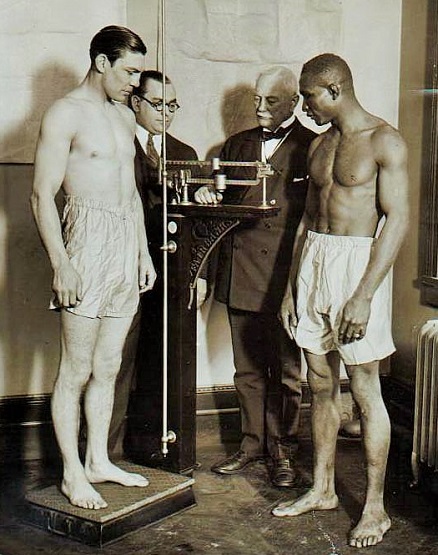

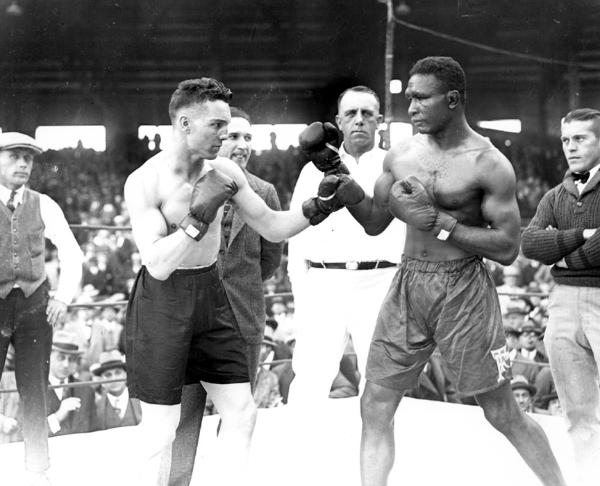

Spurred on by his ability to more than hold his own with the world champion, Tiger persevered. He answered the bell an astonishing 31 times in 1925, beating the likes of Lou Bogash, Jock Malone, Frank Moody and Allentown Joe Gans. In February of 1926 and at New York’s Madison Square Garden he got his second chance at Greb, and this time he made the most of it, winning by unanimous decision. Flowers was the first black American since Jack Johnson to win a world title, the first ever to claim the middleweight championship.

He beat Greb in the rematch six months later though the decision this time was notably unpopular. This would prove the final fight of Greb’s career as just a few months later the legendary “Pittsburgh Windmill” died on the operating table while undergoing minor surgery to reverse facial damage sustained from his boxing career.

As the record book states, Tiger Flowers lost his middleweight title to fellow all-time great Mickey Walker less than four months after the second Greb match, but it’s well-known that the decision in favour of “The Toy Bulldog” was highly questionable, with many first-hand reports declaring Flowers to be the victim of an egregious robbery. Walker avoided a return bout while Tiger went about doing what he always did: fighting frequently and piling up wins. A rematch with Walker was on the horizon when Flowers had surgery performed to remove scar tissue from around his eyes. Sadly, the former champion suffered the same fate as his rival Greb the year before, dying on the operating table from unforeseen complications.

“The Georgia Deacon” is regarded as both an all-time great fighter and one of the finest southpaws to ever step through the ropes. He is, and always will be, a true legend of the ring. — Robert Portis