Prior to 1956, the sight of an Irish woman competing at the Olympic Games was as rare as a summer day in Ireland. This was not merely a reflection of talent; it was an echo of societal constraints that shackled ambition and opportunity for women, not only in sport but at all levels of society.

Until 1956, no Irish woman had ever represented Ireland in track and field at the Olympic Games. The perception of a woman’s role in society was confined to marriage and motherhood. This social norm was clearly evidenced by the 1937 Constitution. Per Article 41.2.2, “the State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.”

In 1924, Phoebe Blair-White and Hilda Wallis competed for Ireland at the Paris Olympic Games. Ireland’s next female Olympian came four years later when Olympic swimmer Marguerite Dockrell competed in Amsterdam. However, it wasn’t until Maeve Kyle burst onto the scene in 1956 that it became acceptable for women to compete in track and field. Kyle paved the way for future generations.

Fast forward to the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, where Ireland had 66 women representing the green jersey – the highest point of female participation. Fifteen Irish women competed in Paris last summer in track and field, highlighting the progress that has been made since 1956.

So when did all this progress begin?

In 1956, Maeve Kyle became the first Irish woman to compete in Olympic track and field events, shattering the glass ceiling that had long confined her predecessors. Her courage, bravery, and unwavering determination were instrumental in redefining societal norms and emboldening other Irish women to pursue their ambitions on a global stage.

Born in Kilkenny in 1928, Maeve was raised in an environment where sport was celebrated, not stifled. Her father, the headmaster of Kilkenny College, fostered a spirit of inclusivity and encouraged her to engage in activities alongside her brothers. “Sport was part of my social life growing up. It didn’t cost you anything. It couldn’t because we had no money!” she would later recall, reflecting on her unorthodox upbringing.

Her early experiences in sport were marked by a fierce determination. “I played touch rugby with the boys. I played hockey with the boys. I swam in the river with the boys. I was convinced I was a boy, too—living in a boy’s school with two brothers.” It was at the age of thirteen, during a school sports day, that her resolve crystallized. “I told Daddy that I wanted to run. ‘I’m not putting on a girls’ event,’ he said. ‘I’ll run against the boys,’ I told him. And I did, and I won. And I won the next year as well.”

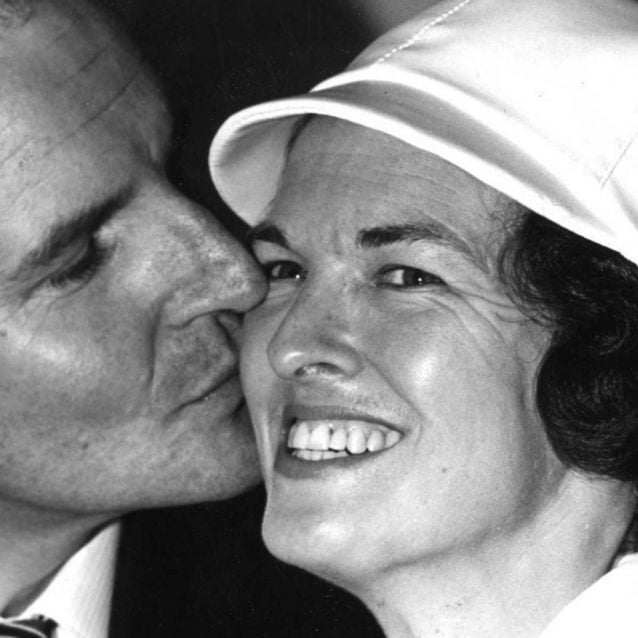

Her prowess on the hockey field became a foundation for her future athletic endeavors. With 58 Irish caps to her name and recognition in the World All-Star team in 1953 and 1959, Maeve established herself as a formidable athlete. Yet, it was a chance encounter at a post-game party that would forever alter the course of her life. There, she met Sean Kyle, who would become her husband and coach, urging her to embrace sprinting as a competitive pursuit.

“Because of hockey, I was introduced to international sport quite early. Then, of course, you get a taste for that level. I was fast enough, fit enough. I had a good enough eye and I had the hunger,” she said, capturing the essence of her transition into track and field. “I remember some ferocious training in the winter. On Christmas Day, I was in the kitchen cooking dinner, and he’d say, ‘You’ve got a 15-minute run to do now before we sit down.’”

As the 1956 Summer Olympics loomed, Sean’s belief in Maeve’s potential grew stronger. “I said to him, ‘Don’t be silly. Ireland doesn’t send women to the Olympics.’ ‘I think they do,’ he replied. ‘In 1948, we sent a female fencer.’” This light-hearted banter belied a profound shift in perception. Kyle was set to make history—not just as a participant, but as a pioneer.

The announcement of her selection to represent Ireland in the Women’s 100m and 200m events was met with an uproar from the public.

“My biggest claim to fame is that I was the first Irish woman to go to the Olympics. You could call me an athletic suffragette, I suppose. Young married women just didn’t go running in foreign lands. They didn’t feed me to the lions, but I’m sure some of them would have wanted to!”

“I was a disgrace to motherhood and the Irish nation,” Maeve recalled with a blend of pride and incredulity.

The societal backlash was palpable; letters in The Irish Times questioned her choices, yet Maeve’s family found humor in the outcry. “People in conservative Ireland did not believe I should be running around the world leaving my husband and children. But my family did not take any notice and thought the letters written to the papers were hilarious. I grew up with a belief I was perfectly entitled to do what the boys were doing.”

With her husband and two-year-old daughter in tow, Maeve embarked on her first international journey. A monumental sum of £200 was needed to fund the trip—a staggering amount in that era. The journey to Melbourne spanned over two weeks, with stops in New York, San Francisco, and Fiji, before they were greeted by a warm welcome from the Australian Irish diaspora.

The Irish team returned home with five medals, yet Maeve’s individual journey was only just beginning. Competing in both the 100m and 200m, she had, after all, run within the confines of what was deemed acceptable for women at the time. “They felt we would require resuscitation if we ran any further,” she chuckled, reflecting on the limitations placed upon her.

It’s worth noting, that up until 1960, women weren’t allowed to run further than 200M at the Olympic Games as it was deemed ‘dangerous to a woman’s health and even fertility.’

Her experiences at the 1956 Olympics catalyzed her development as an athlete. In 1960, she represented Ireland at the Rome Olympics, where the introduction of two new distances for women—400m and 800m—provided her with new opportunities. The 400m became her signature event, a race that she viewed as a complex interplay of strategy and physicality. “To me, the 400 is the greatest event of the lot. You have to stay in your own lane. You’ve got to think. You can’t sprint the whole way. You’ve got to judge and you’ve got to not be influenced by the people either side of you. Those are all serious challenges, both mentally and physically.”

In 1964, Maeve cemented her legacy by becoming Ireland’s first female track and field athlete to compete at three Olympic Games. At 36, she participated in the 400m and 800m, reaching the semi-finals of both. Her relentless pursuit of excellence was unyielding; even at the age of 38, she claimed bronze at the European Indoor Championships in Dortmund with a time of 57.3 seconds.

Bravery is an ancient virtue, often misappropriated in our celebrity-obsessed age. We celebrate athletic courage—be it a daring tackle in football or a decisive penalty kick in the dying moments of a match. Yet true courage can also be found in Maeve’s choice to challenge societal norms at a time when doing so was fraught with risk.

* Quotes obtained from The 2016 Irish Examiner article from Eoin Callaghan.

** Quotes obtained from Turtle Bunburry article.

*** Quotes obtained from The 2013 Irish Independent article from John Costello.